Why Did Hitler Hate Jews? Unmasking the Psychology, Politics, and Propaganda Behind Genocide

Dive deep into the twisted mind of Adolf Hitler. Discover the psychological trauma, political strategies, and deadly propaganda that turned one man’s hatred into the Holocaust. This article uncovers the real reasons behind Nazi antisemitism, Zionism, and the Final Solution. You won’t believe how far it went — and why it still matters today.

Lukas Reinhart

57 min read

Why Hitler Hated the Jews

How could one man’s hatred drag the world into war and genocide? You won’t believe the complex roots of Hitler’s antisemitism…

Introduction – A Dark Question That Still Haunts History

In this introduction, we confront the unsettling question of why Adolf Hitler harbored such venomous hatred toward Jewish people—a hatred that led to the Holocaust and still haunts humanity’s conscience.

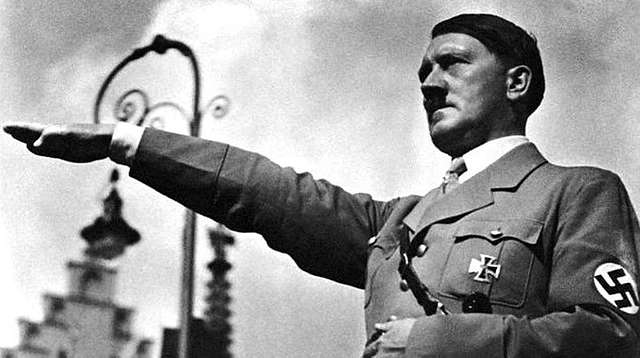

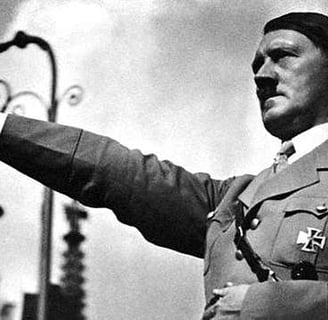

Adolf Hitler’s hatred of the Jews remains one of history’s darkest enigmas. How did a failed artist from Austria develop an obsession so extreme that it fueled World War II and the murder of six million Jews? This question is a dark mystery that still haunts history, forcing us to examine the psychological demons, political propaganda, and deep-rooted prejudices that converged in Hitler’s mind. Understanding why Hitler hated the Jews isn’t just a historical inquiry—it’s a warning of how toxic ideas can take hold of a nation and lead to catastrophe.

From Europe’s long history of antisemitism to Hitler’s personal experiences and the Nazi ideology he crafted, there were many ingredients in this lethal recipe of hate. Hitler’s antisemitism was not an overnight phenomenon. It brewed over decades, stoked by centuries-old conspiracy theories and Germany’s defeat in World War I. By the time he rose to power, Hitler had woven an all-consuming narrative: he cast Jews as the source of Germany’s problems and the eternal enemy of the “Aryan” race. He shouted these beliefs in rally speeches and etched them in the pages of Mein Kampf, leaving no doubt about his deadly intentions. Hitler did not hide his genocidal vision – he broadcast it to the world.

Yet it wasn’t only personal obsession. Hitler also found antisemitism to be a powerful political tool. Scapegoating the Jews gave him someone to blame for Germany’s woes and a convenient “villain” to unite the German people against. This mix of genuine delusion and cold calculation proved devastating. Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels turned Hitler’s prejudices into a relentless media campaign of hate, priming ordinary Germans to accept, and even participate in, persecution. Step by step, what began as hateful words escalated to discriminatory laws and eventually mass murder.

In the sections that follow, we will explore the psychological, political, and historical roots of Hitler’s antisemitism in depth. From the long history of Jew-hatred in Europe that predated him, to his formative years in Vienna, to the impact of World War I’s humiliations, to the poisonous propaganda and Nazi ideology that portrayed Jews as subhuman “enemies of the race,” we’ll trace how Hitler’s hate was formed and how it became the driving force behind the Holocaust. This journey is both fascinating and horrifying – a cautionary tale of how one man’s warped worldview, when combined with political power, led to one of the worst tragedies in human history.

Brace yourself: the shocking facts behind Hitler’s hatred still have the power to horrify – and they must never be forgotten. Share this article to educate others and help ensure that history never repeats itself.

This question is not just historical—it’s a warning. To understand how one man’s hatred led to genocide, we must go back in time, before Hitler even rose to power...

Suggested Article:

➡️ Read: The Rise of Adolf Hitler: From Artist to Dictator

The Roots of Antisemitism in Europe (Pre-Hitler)

In this section, we explore the long history of antisemitism in Europe – centuries of prejudice, myths, and violence that laid the groundwork for Hitler’s extreme hatred of Jews.

To understand Hitler’s antisemitism, we must look at the deep roots of anti-Jewish hatred in Europe. Hitler did not invent hatred of the Jews; he tapped into a well of prejudice that had been filling for over two thousand years. For centuries, Jews were the convenient scapegoats of European society – blamed for everything from ancient plagues to modern economic crises. This dark legacy of antisemitism created a fertile environment for Hitler’s ideas to take hold.

Antisemitism in the Ancient and Medieval World: The story stretches back to the ancient Roman Empire and the Middle Ages. As far back as 70 AD, the Romans destroyed the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem and scattered the Jewish people, viewing their refusal to worship Roman gods as subversive. In medieval Europe, vicious myths took root. The Church often portrayed Jews as “Christ-killers,” and false conspiracy theories abounded – such as the “blood libel” which claimed Jews kidnapped Christian children for ritual murder, or accusations that Jews poisoned wells to spread the Black Death. These outrageous lies sparked massacres and expulsions. England expelled all Jews in 1290; Spain did the same in 1492. Across Europe, Jews were segregated into ghettos and forced to wear identifying badges (a precursor to the yellow star the Nazis would impose). By the time of the Renaissance, the image of Jews as a sinister, alien presence was deeply ingrained in European culture.

Modern Antisemitism and Conspiracy Theories: The Enlightenment and modern era did not erase anti-Jewish hate – in some ways, they intensified it. In the 19th century, as Jews gained civil rights in some countries, a backlash followed. Pseudoscientific racial theories emerged, labeling Jews as an inferior “race” rather than just a religious group. At the same time, Jews were falsely blamed for economic problems. They were stereotyped as greedy bankers or manipulators of finance – even though often Jews were pushed into trades like moneylending because other professions were closed to them. The myth of Jewish wealth and world control reached new heights with the publication of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in 1903 – a notorious fake document claiming that Jews were plotting global domination. This forgery, concocted in Czarist Russia, spread like wildfire. Despite being debunked, it was widely believed and translated into many languages, fueling paranoid conspiracy theories across Europe. In France, the Dreyfus Affair of the 1890s – in which a Jewish army officer was falsely accused of treason – revealed virulent antisemitism in modern society. In the Russian Empire, bloody pogroms (mob attacks) killed thousands of Jews in the late 1800s and early 1900s, prompting many to flee to Western Europe or America.

By the early 20th century, antisemitism was tragically common in Europe – on the political right and left. Many Christian churches had long taught contempt for Jews, and new secular movements carried their own prejudices. Importantly, in the German-speaking lands that Hitler grew up in, antisemitism was part of the cultural air. Austria-Hungary (Hitler’s birthplace) had prominent anti-Jewish politicians like Karl Lueger, the mayor of Vienna, who won votes by railing against “Jewish influence.” Germany’s intellectuals and nationalists often spoke of a “Jewish question” – debating what to do about the Jewish minority in their midst. By World War I, propaganda in Germany painted Jews as disloyal schemers profiteering from the war or spreading communist revolution.

In short, Hitler inherited a toolbox of hateful ideas ready-made for him. Medieval superstition, religious bigotry, and racist pseudoscience all contributed to a toxic image of Jews as the eternal enemy. For over 2,000 years, Jews had been cast as the “other” – the outsider to be blamed when things went wrong. Economic downturn? Blame Jewish bankers. Political unrest? Blame Jewish Bolsheviks. Moral decay? Blame Jewish influence. These prejudices were deeply woven into Europe’s fabric. Hitler’s contribution would be to fuse them into a single, apocalyptic vision – and to act on that hatred with a brutality the world had never seen.

It is chilling to consider that when Hitler began spouting antisemitic bile, many Europeans nodded along because they’d heard similar before. The tragic patterns of history – scapegoating, conspiracy-mongering, religious intolerance – had set the stage. Hitler’s mind would ignite these old hatreds into an inferno. But first, we must examine how Hitler personally came to hate the Jews. What turned this one man into such a fanatic? We turn now to Hitler’s early life for answers.

Antisemitism didn't begin with Hitler—it was centuries in the making. But Hitler turned this ancient hate into modern extermination...

➡️ Explore: How Fascism Rose Across Europe Before WWII

Hitler’s Early Life and First Exposure to Hate

In this section, we look at Hitler’s youth and young adulthood, especially his years in Vienna, to see how early failures and exposure to rampant antisemitism planted the seeds of his hatred toward Jews.

Adolf Hitler did not emerge from the womb a violent antisemite. His journey toward hate began with a troubled early life full of frustrations and failures, during which he gradually absorbed the antisemitic ideas circulating around him. Hitler was born in 1889 in Braunau am Inn, Austria, to a middle-class family. As a boy, he was unremarkable – moody, with a strong interest in art and German nationalism, but he wasn’t yet the ranting demagogue the world would later know. In fact, as a teenager in Linz and early on in Vienna, Hitler even had some Jewish acquaintances and benefactors, suggesting he hadn’t yet formed a deep hatred. So what changed?

Failure and Frustration in Vienna: The turning point came after Hitler’s parents died and he moved to Vienna in 1908 as a young man to pursue his dream of becoming an artist. Vienna was the capital of a multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire and a hotbed of political ideologies – including aggressive German nationalism and antisemitism. Hitler’s life in Vienna was harsh: he twice failed the entrance exam of the Academy of Fine Arts, shattering his dream of an art career. He ended up living in flophouses and shelters, often penniless and selling postcards of his paintings to survive. This was a humiliating period of poverty for the proud young man. Hitler needed someone to blame for his misfortunes, and the multicultural metropolis of Vienna offered easy targets.

Vienna’s streets teemed with right-wing pamphlets and newspapers spewing antisemitism, and Hitler devoured them. Influential figures like Mayor Karl Lueger openly blamed Jews for the city’s problems, and populist agitators scapegoated Jews for everything from housing shortages to socialist movements. Hitler, a sponge for ideas, began to internalize these views. He later claimed in Mein Kampf that Vienna was where he “learned to hate” the Jews. One oft-cited episode (described in Mein Kampf) was when Hitler saw an Orthodox Jewish man with a long black caftan and beard in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt district. At first, Hitler says, he was taken aback – he had never seen an Eastern European Jew before. He wondered, “Is this a German?” Then, as he tells it, “the scales dropped from my eyes.” Hitler wrote that he bought rabid antisemitic pamphlets and soon “wherever I went, I began to see Jews” and saw them as distinct from other humans. He claimed this realization was “the greatest spiritual upheaval” of his life, transforming him from a mild cosmopolitan to a fanatical anti-Semite. In Hitler’s own (possibly self-serving) narrative, this was the moment he found a grand explanation for his personal failures: the Jews.

We should treat Hitler’s recollections with caution – Mein Kampf was propaganda as much as biography. Interestingly, historical evidence suggests Hitler’s antisemitism in Vienna might not have been as strident as he later portrayed. Witnesses who knew him at the time recalled that he even had Jewish friends and benefactors. For example, Jewish merchants and neighbors sometimes helped the destitute Hitler – one Jewish friend gave him a coat, a Jewish charity provided meals at a soup kitchen. Hitler’s beloved mother had been treated kindly by a Jewish doctor (Eduard Bloch), whom Hitler thanked and called an “upright Jew” later. These complexities hint that Hitler’s hatred was not purely born from personal trauma (indeed, no specific Jewish person had harmed him). Rather, it grew as an ideological and psychological crutch: he needed someone to blame for his own lack of success, and antisemitism provided a ready answer.

By the time Hitler left Vienna in 1913, he had embraced the city’s widespread prejudices. He moved to Munich, Germany, still an angry nobody – but now with a head full of vengeful ideas. He had developed an extreme German nationalist identity and saw Jews as the dangerous “other” undermining society. However, it was the crucible of World War I that truly galvanized Hitler’s hatred and set him on the path to power. As we shall see, the war took Hitler’s nascent antisemitism and weaponized it. The next section explores how Germany’s defeat in WWI and a toxic myth of betrayal poured gasoline on Hitler’s fire of hate.

Before moving on, let’s dispel a few myths about Hitler’s antisemitism in his youth. Some have speculated that Hitler’s hatred stemmed from a personal tragedy or hidden secret – rumors that Hitler had a Jewish grandfather, or contracted syphilis from a Jewish prostitute, or was rejected by a Jewish art professor. Serious historians have debunked these theories. Hitler’s antisemitism was not a simple revenge for a personal slight. It was learned from his environment and chosen as a convenient explanation for his and Austria’s struggles. That makes it all the more frightening – because it means ordinary social hate can be absorbed by ordinary people, then amplified by extraordinary ones like Hitler.

In the gutters of Vienna, a bitter failed artist found a scapegoat for all his woes – “the Jew.” This poisonous seed of an idea would lie dormant in Hitler until circumstances allowed it to blossom. World War I provided those circumstances, turning Hitler’s private prejudice into a fanatical crusade. Let’s see how the trauma of war and Germany’s collapse further radicalized Hitler’s hatred.

From the poverty of Vienna to the barracks of WWI, Hitler’s hatred was shaped by pain, propaganda, and personal failure…

➡️ Adolf Hitler: Biography, Nazi Regime, Holocaust

The Impact of WWI and the “Stab in the Back” Myth

In this section, we examine how World War I and Germany’s defeat in 1918 deeply influenced Hitler – transforming his antisemitism from a vague sentiment into a burning mission, fueled by the false “stab-in-the-back” conspiracy that blamed Jews for Germany’s loss.

When World War I erupted in 1914, Adolf Hitler was a 25-year-old drifter eager for purpose. He enlisted in the Bavarian regiment of the German Army and found in war a sense of belonging and meaning he had lacked. By all accounts, Hitler was a brave if unremarkable soldier – he served as a messenger on the Western Front, was wounded, and earned the Iron Cross for bravery. Importantly, during the war Hitler’s political views sharpened. He already harbored nationalist, anti-Jewish leanings from Vienna, but the war gave him focus and rage. Germany’s struggle became personal for him. He later wrote that he viewed the war as a noble fight for Germany’s destiny, and he despised the “internal enemies” he thought were undermining the war effort.

In November 1918, Germany was defeated – and Hitler’s world fell apart. Lying in a hospital (temporarily blinded by a gas attack), Hitler heard the news that the Kaiser had abdicated and an armistice was signed. He described feeling stabbed in the heart by the realization that Germany had surrendered. Like many German veterans, Hitler could not fathom how the once-proud German Army lost. On the battlefield, Germany hadn’t been clearly defeated; the front lines were still on foreign soil when the war ended. So a pernicious explanation took root among angry vets: the “Dolchstoßlegende,” or “stab-in-the-back myth.” This conspiracy theory claimed that Germany’s military didn’t truly lose the war but was betrayed from within by disloyal politicians and populations – namely Jews, socialists, and other “November criminals” who signed the Armistice.

Hitler embraced this myth wholeheartedly. It provided a perfect scapegoat for the humiliation he felt. Rather than accept that Germany was outmatched by the Allies in 1918, Hitler convinced himself that Jews and communists on the home front had “stabbed” the undefeated army in the back. This was, of course, a lie – Germany had been militarily beaten, and the new republican leaders who signed the armistice did so because the generals knew further fighting was futile. But truth didn’t matter to wounded pride. The stab-in-the-back myth combined two of Hitler’s hatreds: Jews and Bolsheviks, often conflated together as a Jewish-Communist treachery undermining Germany. In Hitler’s mind, the Jews were not just an abstract problem now – they were the traitors who robbed Germany of victory and subjected the nation to the shame of the Versailles Treaty.

The years immediately after WWI were chaotic in Germany (the period of the Weimar Republic). There were communist uprisings, violent street fights between political factions, economic collapse, and hunger. In Bavaria, where Hitler settled, a short-lived socialist republic took power in 1919 – and indeed some of its leaders were Jewish. To right-wing nationalists, this seemed to confirm their worst fears: Jews and leftists had caused Germany’s defeat and were now trying to destroy Germany from within. Hitler drank in this toxic atmosphere. In 1919, while still in the army, he was tasked with spying on emerging political groups and came across the German Workers’ Party – a small nationalist, antisemitic party. Hitler famously joined this group (later renaming it the Nazi Party) and quickly rose to prominence with his fiery speeches attacking Jews, Marxists, and the Versailles Treaty.

It’s crucial to grasp how emotional and visceral Hitler’s antisemitism became after WWI. He saw the world in stark, Manichaean terms: Germany (and the “Aryan” race) versus an international Jewish conspiracy. In his worldview, Jews were behind both communism and capitalism, orchestrating Germany’s downfall for their gain. This paranoid belief wasn’t unique to Hitler – many far-right Germans believed versions of it – but Hitler made it his grand theory of everything. As one contemporary noted, Hitler needed an enemy to give meaning to his struggle, and he fixated on Jews as “the universal enemy” responsible for all ills.

The “stab-in-the-back” myth was a pivotal piece of this puzzle. Nazi propaganda endlessly repeated that Jews had betrayed Germany in 1918, a claim used to justify all subsequent persecution. Historian Klaus Fischer wrote that to Hitler, this myth “explained everything” – it turned the complex defeat into a simple narrative of treachery. It also conveniently shifted blame away from German leaders (including the generals) and onto a minority population. This myth was a psychological balm for German wounded pride – and Hitler expertly wielded it.

For Hitler personally, WWI’s end was a kind of psychological trauma. He later said that hearing of the surrender was when he resolved to enter politics: to “rescue Germany” and punish those who betrayed it. He felt personally stabbed in the back, and he projected that rage onto the Jewish community. Hitler’s antisemitism thus went from a generalized prejudice to a burning vendetta after WWI. Biographers note that by 1919–1920, Hitler spoke of Jews with obsessive hatred, describing them as bacteria and “vampires” sucking the life from Germany. He began advocating not just removing Jews from power but eliminating them entirely from German society.

One striking illustration: In September 1919, Hitler wrote a letter (the Gemlich letter) where he stated that the Jewish question could only be solved by “removing” all Jews from Germany – one of his first written expressions of what would become genocide. Already, the fantasy of “purifying” Germany through the expulsion or destruction of Jews was forming in his mind. This was just a year after the war, long before Hitler had any power. It shows how the combination of war defeat and the stab-in-the-back lie had radicalized him to the core.

Another consequence of WWI was that Hitler found his voice and audience. The postwar instability gave rise to extremist groups, and Hitler – a gifted orator fueled by genuine anger – mesmerized audiences with his speeches. He would shout about how Jews had conspired to bring about Germany’s ruin and how he would root out this “enemy within.” Listeners, themselves desperate to explain the loss and economic ruin, responded enthusiastically. Each time Hitler repeated the lie, it gained more traction. By exploiting the stab-in-the-back myth, Hitler was able to mainstream antisemitism in a new way: not just as age-old religious prejudice, but as a seemingly plausible political explanation for Germany’s misery. This was a critical step. It transformed antisemitism from hate for hate’s sake into a rallying cry for national salvation (in the warped view of Hitler and his followers).

In summary, World War I lit the fuse of Hitler’s hatred. The war’s end filled him with humiliation and anger, and the myth that Jews betrayed the nation gave that anger a target. Hitler emerged from WWI convinced that his life’s mission was to avenge Germany by combating the alleged Jewish “enemy” from within. He would carry this mission into the 1920s as he built up the Nazi Party. And in prison in 1924, after a failed coup, Hitler poured all these ideas into a book that would become the bible of Nazism – Mein Kampf. In that book, Hitler laid out explicitly why he hated Jews and what he intended to do about it. It was nothing less than a written declaration of hatred and intent. Let’s delve into Mein Kampf next, to see how Hitler justified his antisemitism in his own words.

Germany’s defeat in WWI left deep scars—and Hitler used those wounds as fuel for his hatred…

➡️ The Role of World War I in Shaping Adolf Hitler’s Ideology

Mein Kampf – Hitler’s Written Declaration of Hatred

In this section, we examine Hitler’s infamous book Mein Kampf, written in 1924–25, where he openly declared his hatred for Jews and outlined the antisemitic ideology that would later guide Nazi policy.

While languishing in Landsberg Prison in 1924 after a failed coup attempt, Adolf Hitler took pen to paper and wrote Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”). Part autobiography, part political manifesto, this hefty tome is essentially Hitler’s blueprint for the Nazi movement. It is also a chilling declaration of hatred, in which Hitler spells out exactly what he thinks of Jews and what he believes should be done to them. If anyone had bothered to take Mein Kampf seriously at the time, the Holocaust might not have been such a “surprise” – because Hitler practically telegraphed his intentions within its pages. Hitler put his hate in writing for all to read – an unparalleled warning that tragically went unheeded.

Mein Kampf is a meandering work, but certain themes come through loud and clear. One of the strongest is Hitler’s virulent antisemitism. In the book, Hitler doesn’t just criticize Jews – he demonizes them as the source of all evil. He refers to Jews as a parasite on nations, a “race-tuberculosis of the peoples” that undermines healthy society. He insists that Jews are not a religious group but a toxic race, inherently corrupt and out to dominate the world. Over and over, Hitler paints Jews as the antithesis of everything good: if Germans represent culture, honor, and productivity, then (in Hitler’s twisted view) Jews represent decay, deceit, and destruction.

A key concept in Mein Kampf is the idea of racial struggle. Hitler believed history was a Darwinian fight for survival between races. He idolized what he called the Aryan race (which to him meant the Germanic, Nordic peoples) as the creators of all great civilization. And he cast the Jews as the polar opposite – a “racial enemy” bent on tearing down Aryan achievement. In one infamous passage, Hitler claims that if the Jews were to win, the result would be the end of humanity: “If with the help of his Marxist creed the Jew triumphs over the peoples of the world, then his crown will be the funeral wreath of humanity.” (He goes on to say that by resisting the Jew, he believes he is doing “the Lord’s work” – a grotesque self-justification invoking God.)

What exactly did Hitler accuse the Jews of? Virtually everything. He blamed Jews for Germany’s defeat in WWI, alleging that Jewish financiers and communists conspired to bring about the collapse. He blamed Jews for the rise of Marxism/Bolshevism – referring constantly to “Jewish Marxists” and claiming communism was a Jewish plot to destroy nations. At the same time, he also blamed Jews for exploiting capitalism to their advantage and orchestrating economic crises. This contradictory trope – Jews were simultaneously behind communism and high finance – did not bother Hitler; it was common in far-right circles who imagined a Jewish conspiracy so vast that it controlled both ends of the political spectrum. Hitler wrote that “the Jewish youth lies in wait for hours on end… spying on the unsuspicious German girl he plans to seduce, adulterating her blood” – a particularly vile example of his obsession with racial “purity” and fear of Jews “corrupting” Aryan bloodlines.

Throughout Mein Kampf, Hitler makes clear that he considers the Jews an existential threat to Germany and the Aryan race. He calls them “a parasite in the body of other nations” that must be removed. He even compares Jews to germs: just as one would eliminate a deadly bacillus to protect a healthy body, Hitler argues one must eliminate the Jew to protect society. It’s stomach-turning rhetoric, but it’s important to confront because it laid the intellectual groundwork for genocide. When you’ve already dehumanized a group as diseased “parasites,” it’s not far to jump to the conclusion that they should be exterminated like pests.

Another aspect of Mein Kampf is Hitler’s ruthless tone – he doesn’t shy away from violence. He describes how the use of poison gas against Jews would have been preferable to Germany losing WWI (a horrifying foreshadowing). He writes that the German government must undertake “the deliberate and systematic combating and extirpation of the Jewish people.” The word “extirpation” means total removal by the roots – a thinly veiled reference to eradicating Jews entirely. This was a written prophecy of the Holocaust.

It’s also notable that Mein Kampf was published in two volumes (1925 and 1926) and eventually sold millions of copies (though many buyers didn’t read it fully). Hitler’s ideas were not secret. By 1933, Mein Kampf was widely available. Yet many Germans and world leaders dismissed it as ranting that Hitler wouldn’t actually act on. That complacency proved fatal.

To highlight specific content: In Mein Kampf, Hitler asserted that Germany had to purify itself by removing Jews. He considered this a matter of national survival. For example, he argued that all great civilizations collapsed because they allowed racial mixing and that Germany’s renewed greatness depended on “care for the purity of our blood”. This was the pseudo-scientific racism talking – influenced by eugenics and Social Darwinist ideas popular at the time. Hitler took those concepts to an extreme, insisting that Jews were “chaff” to be discarded from the human gene pool.

Hitler also outlined “Lebensraum” (living space) in Mein Kampf – the idea that Germans needed to expand eastward at the expense of “inferior” Slavs. Why mention that here? Because Hitler linked his antisemitism to this expansionist vision. He argued that Jewish influence was preventing Germany from achieving its destiny; only by defeating “the Jew” could Germany unite and conquer new lands. He even accused Jews of controlling the Soviet Union – the specter of “Judeo-Bolshevism” – thus tying antisemitism directly to his future war plans in the East. In Hitler’s mind, invading Poland and Russia would both gain land and crush the center of Jewish power (since millions of Jews lived in Eastern Europe). This lethal merging of racist ideology and geopolitical strategy meant that Hitler’s war against the Allies would always also be a war against the Jews.

In summary, Mein Kampf was Hitler’s manifesto of hate. It catalogued his prejudices and laid out a roadmap: strip Jews of rights, remove them from society, and eliminate their presence as a “poison” in Germany. Many at the time found the book extreme, even absurd. But devoted Nazis took it seriously, and when Hitler came to power, Mein Kampf turned from words on a page to official policy.

One can quote Mein Kampf at length, but perhaps a chilling line will suffice: “If at the beginning of the war and during the war, twelve or fifteen thousand of these Hebrew corrupters of the nation had been subjected to poison gas, the sacrifice of millions at the front would not have been in vain.” Here Hitler explicitly suggests that gassing Jews during WWI would have saved German lives. It’s an eerie prelude to the gas chambers of WWII. Hitler was telling the world, in black and white, what he wanted to do. Tragically, too few believed he meant it.

Having examined Mein Kampf, we see that by the mid-1920s Hitler’s antisemitic ideology was fully formed and uncompromising. The next step is to see how these ideas became the doctrine of the Nazi Party and the German state. Hitler did not hate alone – he indoctrinated an entire movement with the notion that Jews were the “eternal enemy.” Let’s explore how Nazi ideology turned antisemitism into a guiding principle of a government, and how propaganda and policy systematically implemented Hitler’s hateful vision.

“Mein Kampf” wasn’t just a book—it was a bomb waiting to go off. Every page was fuel for future genocide...

Suggested Article:

➡️ Read Next: Inside Mein Kampf: Hitler’s Radical Ideas Decoded

Nazi Ideology: Jews as the “Eternal Enemy”

In this section, we discuss how antisemitism became a central pillar of Nazi ideology. The Nazi worldview cast Jews as the “eternal enemy” of the German (Aryan) people, requiring their elimination. We examine the components of this ideology and how it justified relentless persecution.

When Adolf Hitler and the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, the antisemitic rantings of Mein Kampf became the basis for state ideology. Under Nazi rule, Jews were officially labeled the eternal enemy of the German people. Nazi ideology was built on a myth of racial struggle: a heroic “Aryan” race defending itself against subversive races, above all the Jews. In Nazi propaganda and doctrine, Jews were not just another group – they were portrayed as an almost supernatural force of evil that had persisted through history to plague mankind. This apocalyptic framing helped justify extreme measures. After all, if you genuinely believe a certain group is an existential threat to civilization, any action against them can be painted as “self-defense.”

Racial Theory and the Aryan Myth: At the heart of Nazi belief was a hierarchy of races. Hitler and his chief ideologues (like Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels) glorified the Aryan race – which they identified mainly with Germans – as the creator of all noble culture. They borrowed pseudo-scientific racial theories from earlier thinkers (like Houston Stewart Chamberlain) which claimed that Aryans were biologically superior. In contrast, they described Jews as racially inferior and parasitic. To Nazis, the Jew was uniquely dangerous: not only “subhuman” (an Untermensch), but cunning, patient, and forever conspiring to undermine superior races. In a grotesque metaphor often used, Jews were “the maggots in the corpse” or “the bacillus infecting a healthy body” of nations. Nazi school textbooks taught children to recognize and hate the so-called racial features of Jews. Biology classes measured skull sizes and nose shapes, promoting the lie that Jews were biologically different and dangerous. Nazi ideology essentially dehumanized Jews – a critical step that made it psychologically easier for Germans to accept violence against them.

The “Eternal Jew” Conspiracy: The Nazis took old conspiracy theories about Jews and amplified them with a modern propaganda machine. They perpetuated the idea of an international Jewish conspiracy – that “the Jews” were secretly controlling governments, banks, and spreading both communism and decadent capitalism to destroy nations. Hitler firmly believed (or at least professed to believe) that Jews were behind both the Soviet Union and Western plutocracies, a dual threat to Germany. Nazi speeches and media endlessly harped on this: Jews as the invisible hand orchestrating Germany’s defeat in WWI, the hyperinflation of the 1920s, the Great Depression, and the rise of Bolshevism. One famous Nazi propaganda film was literally titled “Der Ewige Jude” – “The Eternal Jew.” It portrayed Jews as wandering cultural parasites who infiltrate societies, comparing them to rats sneaking into homes. The message was that this “eternal Jew” had been the enemy of civilization throughout history – from the days of ancient Egypt through the Middle Ages to modern times – always allegedly causing ruin. By casting Jews as a timeless, unchanging malignant force, the Nazis gave their followers a sense of historical mission: to finally rid the world of this menace.

Anti-Bolshevism and Anti-Capitalism through an Antisemitic Lens: Nazi ideology was opportunistic in blaming Jews for whatever the Nazis opposed. They hated communism – so they called it Judeo-Bolshevism and pointed out that some early communist leaders (like Karl Marx or Soviet commissars) were of Jewish origin. They hated what they saw as exploitative finance capitalism – so they talked of Jewish bankers and the “Jewish stock exchange” in the same breath. This led to bizarre contradictions: Nazi propaganda would condemn Jews for being behind both the socialist uprisings and behind greedy big banks. Logic wasn’t the point; the point was that Jews = “the enemy behind everything we don’t like.” For example, Joseph Goebbels wrote in 1941: “If the Allied statesmen declare that they are fighting against Nazism, they mean they are fighting against us, against the German people. But who is behind these statesmen? The Jews!” Such rhetoric convinced many Germans that every threat or hardship could be traced back to Jewish machinations, making antisemitism a unifying theory for the Nazi worldview.

Religious Antisemitism Turned Racial: Traditionally, anti-Jewish sentiment in Europe had a religious component (Christians vs. Jews). The Nazis secularized and racialized this. They didn’t care if a Jew converted to Christianity – in Nazi law, “a Jew is a Jew by blood.” The 1935 Nuremberg Laws defined anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents as a Jew, regardless of self-identity or belief. This was unprecedented: people who had fully assimilated and even whose families had converted generations back were still marked as Jews if their lineage fit the criteria. This shows how Nazi ideology regarded Jewishness as an immutable biological trait, and Jews as an alien race that could never truly be German. Marriages and sexual relations between Jews and Germans were outlawed (to prevent “contamination” of Aryan blood). This obsession with blood purity was a core Nazi tenet – they framed their antisemitic campaign almost like a health initiative for the nation’s gene pool.

The Culture War – Jews as Subverters: The Nazis also attacked Jews as the supposed drivers of cultural degeneration. In Nazi rhetoric, whatever art or music they disapproved of (like modernist art, jazz, etc.) was labeled “degenerate” and often linked to Jewish influence. For instance, they claimed the decadence of 1920s Weimar Germany (cabarets, liberal sexual attitudes, etc.) was due to Jewish cosmopolitan influence in media and entertainment. Thus, Hitler’s hatred was not only political but also cultural. He believed (or said he did) that Jews were “corrupting” the purity of German culture and morality. This was just another front in the battle – the Nazi crusade was to purify culture, politics, economy, and biology all at once by eliminating Jewish influence. Jews were the total enemy in Nazi ideology: race enemies, class enemies, religious enemies, cultural enemies, all rolled into one.

Us vs. Them – the Nazi Rallying Cry: By portraying Jews as an existential threat, the Nazi leadership fostered an extreme us-versus-them mentality in the German population. It wasn’t enough to marginalize or even expel Jews; Hitler’s rhetoric suggested that if Jews remained alive and active anywhere, they would somehow regroup and harm Germany. In a January 1939 speech, Hitler went so far as to “prophesy” that if another world war broke out, the result would be “the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe”. This chilling statement, which many at the time dismissed as bluster, revealed how deeply Hitler equated war against nations with war against Jews. For the Nazis, defeating external enemies (like Britain or the Soviet Union) was intertwined with destroying the internal/eternal enemy (the Jews). It’s as if they couldn’t imagine one victory without the other.

To ordinary Germans under Nazi rule, these ideological constructs were hammered home continuously through education, propaganda, and even leisure activities. Children joined the Hitler Youth where they were taught songs with lyrics like “Sharpen the long knives on the pavement, let the knives slip into the Jew’s body” (a Hitler Youth song line). Posters showed monstrous caricatures of Jewish faces looming over the globe. Newspapers like Der Stürmer ran lurid stories of Jewish crimes (mostly fabricated) and always ended with the tagline “Die Juden sind unser Unglück!” – “The Jews are our misfortune!”. Imagine hearing that day in and day out. Over years, it had a potent effect: by the late 1930s, a significant portion of the German public either actively hated Jews or was at least conditioned to view them as “less than” and to turn a blind eye to their persecution.

Thus, by the time war began in 1939, Nazi Germany was ideologically primed for something unthinkable. Hitler had identified the “eternal enemy” and convinced his country (and perhaps himself) that eliminating this enemy was not only necessary but righteous. Nazi ideology had effectively transformed age-old antisemitism into a secular jihad. Jews were no longer just people of a different faith – they were an existential virus to be eradicated for the sake of the world. With that mindset at the helm of a powerful industrial nation, the stage was set for genocide.

Before we get to the genocide itself, we should examine the tools the Nazis used to instill and heighten this hatred in the populace – namely, Goebbels’ propaganda and psychological warfare. How do you take radical antisemitism and sell it to an entire nation? The Nazis, sadly, were masters of that dark art. We will now explore the propaganda machinery that turned Nazi ideology into mass persuasion, ensuring that millions of Germans would go along with or actively participate in the persecution of their Jewish neighbors.

By framing Jews as an existential threat, Nazi ideology gave Hitler both purpose and permission to unleash genocide…

➡️ Why Hitler Hated Jews: Nazi Ideology & Zionism Explained

Goebbels, Propaganda, and Psychological Warfare

In this section, we look at how Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and the Nazi state unleashed a sophisticated propaganda campaign to demonize Jews. We explore the psychological tactics – scapegoating, fear-mongering, repetition – that conditioned ordinary Germans to accept, and even applaud, the persecution of Jews.

Adolf Hitler once said, “Propaganda is a truly terrible weapon in the hands of an expert.” In Nazi Germany, that expert was Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment. If Hitler provided the hateful content (Jews are evil, Jews are our misfortune, etc.), Goebbels ensured that content was skillfully packaged and blasted across Germany relentlessly. The Nazi propaganda machine was unprecedented in its reach and sophistication for its time. It monopolized all forms of media – newspapers, radio, films, posters, rallies, even school curricula – to manipulate public opinion and incite hatred. Goebbels understood that to get a population to eventually condone mass violence, you first had to saturate them with fear and loathing toward the chosen victim group. And that’s exactly what he did.

Scapegoating and Simplification: Goebbels’ propaganda playbook emphasized simple messages repeated over and over. One of his core techniques was scapegoating: blaming a group for all problems. In Nazi propaganda, every German problem was the fault of the Jews. Unemployment? The Jews. Communist unrest? The Jews. Moral decline? The Jews. Loss of WWI? The Jews (with the “stab-in-the-back” betrayal narrative). By hammering this single point endlessly, the Nazis fixed in the German psyche an automatic reaction: if something’s wrong, blame the Jews. This was psychologically comforting to many – it’s easier to blame a scapegoat than to deal with complex issues or one’s own failures. Goebbels knew this and exploited it masterfully.

He reduced everything to “us vs. them”. In speeches and articles, he painted a mythic picture: on one side, the innocent, noble German Volk trying to rebuild and live in peace; on the other, the conniving Jew plotting Germany’s ruin from the shadows. He turned Jews into a boogeyman for the German public. As one commentator summarized Nazi propaganda, it “emotionally charged messages with fear, scapegoating and repetition until lies felt like truth”.

Emotional Appeals and Fear-Mongering: Nazi propaganda was deliberately emotional, not rational. Goebbels openly scorned factual argument; he believed people are moved by feelings, not logic. So his ministry churned out content designed to make Germans feel afraid, angry, and eventually murderous toward Jews. They played up old prejudices (e.g., medieval blood libel tropes re-emerged in children’s books portraying Jews kidnapping German children – vile stuff). They created new fears: claiming, for instance, that Jews were spies or saboteurs ready to stab Germany in the back again, or that Jewish bankers were plotting to starve German families. Constant repetition of phrases like “Jewish menace” or “world Jewry” or “racial pollution” drummed these fears into the populace.

A prime example of fear-based propaganda was the portrayal of Jewish men as a threat to German women – the racist trope of the predatory Jewish male. Nazi films and posters often insinuated that Jewish men lurked to defile Aryan women, linking antisemitism to sexual panic and “racial purity” concerns. This stoked disgust and protective anger, especially among male viewers, and justified the later laws banning intermarriage.

Another example is the notion that Jews were planning a genocide of Germans – yes, the Nazis claimed the Jews intended to do to Germans what the Nazis were in fact planning for Jews. This twisted projection made ordinary Germans feel it was kill or be killed. In Goebbels’ words in 1941: “The Jews want our people’s extermination. We are defending ourselves.” Such lies created a climate of self-righteous paranoia – Germans were told they had to strike first to prevent their own annihilation by the Jews. It’s an appalling reversal of victim and aggressor, but it was effective at removing moral hesitation.

Total Media Control and Repetition: Goebbels centralized all German media under Nazi control. Editors and radio broadcasters were either Nazi loyalists or took direct orders on what to publish. Opposition voices were silenced – no free press remained. This meant the Nazi message was monolithic and ubiquitous. A German citizen in 1930s could hardly escape it: the newspaper at breakfast had antisemitic cartoons; the radio talk show in afternoon warned of the “Jewish Bolshevik threat”; newsreels before movies spewed conspiracy theories; school lessons taught racial science comparing “Aryan skulls” to “Jewish skulls.” When you hear the same thing everywhere, it starts to feel true, or at least becomes the unquestioned background of life.

Goebbels famously said, “A lie told once remains a lie, but a lie told a thousand times becomes the truth.” One can see this in the gradual acceptance of radical measures against Jews. At first, many Germans may have thought Nazi rhetoric was harsh. But as they were barraged with one-sided information (Jews as criminals, diseases, traitors, etc.), more and more people either came to believe it or at least didn’t object when Jews were humiliated, stripped of rights, and later removed entirely from communities. Year by year, propaganda de-sensitized the German public to Jewish suffering. Neighbors who had lived alongside Jews for years suddenly viewed them with suspicion or contempt. A 1933 boycott of Jewish shops had ordinary Germans shouting “Don’t buy from Jews!” outside stores. By 1938’s Kristallnacht pogrom, many Germans stood by as Jewish stores were smashed and synagogues burned, some even cheered – a result in large part of five years of intensive propagandistic conditioning.

Cult of Personality and Social Pressure: Propaganda also built up Hitler as an infallible savior and equated loyalty to Hitler with loyalty to Germany. This meant that agreeing with Hitler’s hatred became a form of patriotism. If you harbored doubts about persecuting Jews, you risked being seen as disloyal or un-German. Social conformity and groupthink took over – if everyone around you is giving the Nazi salute and nodding along to antisemitic slogans, the pressure to join in is immense. Goebbels’ rallies and spectacular events (like the Nuremberg party rallies filmed in Triumph of the Will) created an emotional collective high, merging the individual into a sea of Nazi flags and chants. In those moments, critical thinking was drowned in a surge of tribal fervor. Psychological warfare tactics made dissent feel impossible; many Germans likely went along with antisemitic measures partly because they saw everyone else doing so and because propaganda convinced them that any dissent would be siding with “the enemy.”

Goebbels also censored opposing viewpoints rigorously. Germans were largely cut off from hearing sympathetic views about Jews or learning about Jewish contributions to society. Jewish voices themselves were silenced as Jewish journalists were fired, Jewish books burned, and eventually Jews banned from speaking publicly. Thus, negative stereotypes went unchallenged.

“An Atmosphere of Fear and Hatred”: By the late 1930s, Goebbels had succeeded in creating what one historian called “an atmosphere of fear and hatred” in Germany. Fear of what Jews might do, hatred for what they were said to have already done, permeated society to the point that radical action against Jews seemed not only acceptable but necessary. Propaganda primed the public for violence: cartoons regularly depicted Jews as rats to be exterminated; newspaper articles talked of a coming “Final Solution” to the Jewish question in vague terms even before war started. Many average Germans probably didn’t want to personally harm anyone – but by the time violence escalated, they had been conditioned to see Jews as not really fellow human beings. This is the terrible power of propaganda: to strip the victim group of their humanity in the eyes of bystanders. Once that is achieved, the rest – the ghettos, the camps, the gas chambers – can occur with far less public resistance.

To illustrate, consider Kristallnacht (the Night of Broken Glass) in November 1938. This was a nationwide pogrom where Nazi paramilitaries attacked Jewish businesses, synagogues, and homes, killing nearly 100 Jews and arresting 30,000. This event was presented by Nazi propaganda as a spontaneous “outrage” of the German people over a minor assassination (actually orchestrated by the Nazis). In truth, it was a planned bout of terror. What’s noteworthy is how the general public responded: many were passive, some even joined the looting, and there was no widespread outcry. Years of hearing that “the Jews are our misfortune” had done their grim work. A shocking fact: the morning after Kristallnacht, German newspapers largely praised the action or blamed Jews for it. Goebbels spun it as, essentially, “serves them right.” Imagine the psychological impact – the last moral barriers were being removed. If burning synagogues is acceptable, what isn’t?

In summary, Nazi propaganda under Goebbels was the engine that drove ordinary people to either condone or actively participate in extraordinary evil. By manipulating emotions and controlling narratives, it made Hitler’s extreme antisemitism seem “normal” and even patriotic. This propaganda onslaught is a sobering lesson in how hate can be mass-produced. It is often said that the Holocaust was possible not just because of Hitler’s orders, but because an entire society had been prepped to look the other way – or even help – as their Jewish neighbors were taken away.

With the public thoroughly conditioned, the Nazis moved from words to deeds. They encoded their hatred into law – officially excluding Jews from society and stripping them of rights. Let’s now examine the legal discrimination, particularly the Nuremberg Laws, which laid the groundwork for the “Final Solution.” We will see how hatred moved from propaganda posters into the statute books, turning bigotry into government policy.

Understanding Hitler’s hatred helps us recognize modern forms of antisemitism before they escalate…

➡️ Fascism in Europe: How Mussolini, Hitler & Franco Shaped the 20th Century

The Nuremberg Laws and Legal Discrimination

In this section, we discuss how Nazi hatred of Jews was enshrined in law. We focus on the 1935 Nuremberg Laws and other anti-Jewish legislation that systematically stripped Jews of their rights, marking a transition from propaganda to official persecution. These laws isolated Jews socially and economically, setting the stage for later violence.

By 1933, Hitler had seized power as Germany’s Chancellor. Almost immediately, the Nazi regime began translating its antisemitic ideology into concrete policies. In the spring of 1933, Nazi stormtroopers stood in front of Jewish-owned shops with signs saying “Don’t Buy from Jews!” and a nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses was conducted (April 1, 1933). This was the first organized action to economically strangle Jews. Though the one-day boycott was not massively successful and wasn’t sustained at that time, it signaled the regime’s intentions. Soon came laws expelling Jews from the civil service, universities, law, medicine, and other professions. A 1933 law forbade Jews from working as government officials (the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service), causing thousands to lose their jobs. By 1934–35, Jews were banned from serving in the military, from owning farmland, and even from things like marrying “Aryan” Germans (even before Nuremberg, some local ordinances tried to stop mixed marriages).

The culmination of this piecemeal approach was the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. Announced at the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg in September 1935, these laws codified racial antisemitism into the German legal code. There were two main laws: the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor.

The Reich Citizenship Law declared that only people of “German or related blood” could be citizens of Germany. Jews, therefore, were reduced to mere “subjects” of the state with no citizenship rights. This law effectively stripped Jews of basic civil rights – they could no longer vote, hold public office, or enjoy legal protections of citizenship. A Jew in Nazi Germany after 1935 was a non-person in the eyes of the law.

The Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor forbade marriages and extramarital relations between Jews and “Aryans”. Marriages already existing were not immediately dissolved (some were later under pressure), but no new such unions were allowed. It also banned Jews from employing German maids under age 45 (a twisted measure to prevent supposed sexual contact). Additionally, Jews were forbidden from displaying the German flag (because they were deemed unworthy).

To enforce these laws, the Nazis had to define “Who is a Jew?” They did so with perverse precision: anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jew, regardless of whether they themselves practiced Judaism or even identified as Jewish. People with two Jewish grandparents were considered “Mischlinge” (mixed blood) of first degree – partial Jews with a somewhat intermediate status; one Jewish grandparent made you a Mischling of second degree. These bureaucratic racial definitions tore through families. For instance, a half-Jewish person (two grandparents) might avoid some legal restrictions initially, but their full-Jewish relatives (three or four grandparents) would be immediately marginalized. This created tragic situations where decorated WWI veterans who had been fully integrated in society suddenly found themselves labeled non-Aryan and cast out.

The impact of the Nuremberg Laws was devastating. In one stroke, they made clear that Jews had no future in Germany. Signs went up reading “Jews Not Wanted” in stores, parks, even towns (some towns declared themselves “Jew-free”). Jews could not attend public theaters or cinemas. Hospitals began refusing Jewish patients. Jewish children were eventually banned from public schools (by 1938). Each month brought new edicts: Jews required to register assets, Jews barred from receiving health insurance reimbursements, Jewish lawyers and doctors forbidden to have Aryan clients or patients. The Nazi goal was to squeeze Jews out of every sphere of life – social, economic, cultural – and force them to emigrate. Indeed, from 1933 to 1939, hundreds of thousands of Jews fled Germany (about half the German Jewish population left, despite difficulties in finding refuge abroad). Those who remained often did so because they were elderly, poor, or simply hopeful that “this madness will pass.” Tragically, it was only the beginning.

One chilling aspect of this legal discrimination was how quickly many Germans adapted to it. Longtime Jewish neighbors suddenly couldn’t ride the same buses or go to the same cafes, and many non-Jews just accepted that as normal. Propaganda and years of gradual pressure had done their work, as discussed earlier.

Kristallnacht – The Night of Broken Glass (1938): Over the years 1935-1938, the segregation and impoverishment of Jews intensified. Jews were forced to register their businesses and then pressured to sell them cheap to Aryans (a process called “Aryanization”). By late 1938, Jews had lost an estimated two-thirds of their property. On November 9-10, 1938, the discrimination turned violently overt with Kristallnacht, the state-orchestrated pogrom mentioned earlier. Nazi mobs destroyed over 7,000 Jewish businesses, burned more than 250 synagogues, killed around 91 Jews, and vandalized Jewish hospitals, schools, and homes. About 30,000 Jewish men were rounded up and sent to concentration camps (Dachau, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen) where many were brutalized; some were released weeks or months later on condition of trying to leave Germany.

Kristallnacht was a turning point because it made clear that the Nazis’ end goal was not just segregation but elimination of Jews from Germany entirely. After the pogrom, additional decrees came: Jews were fined 1 billion Reichsmarks collectively for the damage of Kristallnacht (the ultimate insult: making the victims pay for the violence). Jews were banned from owning firearms (defenselessness enshrined). Jewish children still in public schools were expelled. Curfews were imposed on Jews. And crucially, a decree in 1939 forced Jews to adopt new middle names: “Israel” for men and “Sara” for women – marking them clearly as Jews on any identity papers. Not long after, Jews were required to carry special ID cards with a large red “J” stamp, and by 1941 to wear the yellow Star of David badge on their clothing at all times. The badge – emblazoned with “Jude” (Jew) – was perhaps the most humiliating symbol of their pariah status, an idea lifted from medieval practices and now applied with modern efficiency.

All these laws and measures served a few purposes in the Nazi plan: isolation, identification, and dehumanization. By isolating Jews from society, it became easier for Nazis to consider more radical “solutions” without public interference. By identifying and concentrating Jews (through registration and badges), it became easier logistically to round them up. And by legally defining them as sub-citizens, it paved the way for stripping them not only of rights but of property, freedom, and eventually life.

It’s important to realize that each new law or decree also tested the waters of public opinion. When the Nuremberg Laws passed and most Germans went along, the regime was emboldened to go further. When Kristallnacht’s violence met little resistance (in fact, many ordinary Germans were appalled by the destruction, but they felt powerless or intimidated to oppose it openly), the Nazis learned they could get away with mass violence too. Step by step, the path to genocide was laid. One Nazi official, surveying the broken glass and ruins after Kristallnacht, remarked that this was the “beginning of the final solution of the Jewish question.” Note the phrase “Final Solution” – it would soon take on a literal, horrifying meaning.

Picture the scene: a burnt-out synagogue, its blackened beams silhouetted against the morning sky; shards of glass from Jewish shop windows littering the streets like crystals – hence “Night of Broken Glass.” That image of destruction was a harbinger of far worse to come. Burned-out synagogue in Frankfurt-Höchst after Kristallnacht, November 1938. This “legal” hatred spilling into open violence foreshadowed the genocide to follow.

By 1939, on the eve of World War II, Germany had completely marginalized its Jewish population. Roughly 300,000 Jews remained in Germany (down from 525,000 in 1933), many of them elderly or unable to secure visas to escape. They lived in fear and desperation, effectively trapped. Hitler had achieved domestically what he promised: Jews were segregated and rendered defenseless. But now he controlled vast new territories as the war began – Poland, with its 3 million Jews, and other lands. What to do with all these Jews under Nazi control? That’s when the regime’s antisemitic project entered its most lethal phase: the plan to physically annihilate the Jews of Europe, euphemistically termed “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question.”

Our next section will explore how Hitler’s hatred, implemented stepwise through law and terror as we’ve seen, escalated during World War II into the genocide known as the Holocaust. We will trace how discrimination turned to mass murder – and how the mechanisms of industrialized killing were justified under the same poisonous logic that “the Jews are our misfortune.” It’s a grim story, but a necessary one to complete the answer to why Hitler’s hatred mattered so much: because it was translated into action on an unthinkable scale.

The Final Solution: How Hatred Became Genocide

In this section, we detail how Hitler’s hatred of Jews culminated in the “Final Solution” – the systematic genocide of Europe’s Jews during World War II. We examine the steps from ghettos to mass shootings to extermination camps, and Hitler’s own role in turning decades of antisemitic ideology into the reality of the Holocaust.

All the propaganda, laws, and terror we’ve discussed were building toward an unspeakably violent climax. When World War II erupted in 1939, the Nazis suddenly had millions more Jews under their control as they conquered Poland and later the Soviet territories. The question for Hitler and his top henchmen became: what to do with all these people whom they deemed their ultimate enemies? Initially, Nazi plans considered forced mass emigration or deportation of Jews to distant places (like the ill-conceived Madagascar Plan). But war provided new “opportunities” – cover for far more ruthless solutions that would have been impossible in peacetime. Emboldened by battlefield successes and obscured by the fog of war, the Nazi regime moved from persecution to annihilation.

Hitler had hinted at genocide even before the war. Recall his January 30, 1939 Reichstag speech: “If the international Jewish financiers… succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.” This “prophecy,” as he called it, was repeated during the war as if to justify what was happening. Indeed, after war began, Nazi propaganda started referencing Hitler’s prophecy and implying it was being fulfilled. So while Hitler seldom gave clear written orders like “exterminate all Jews” (the Nazis kept such directives mostly verbal and secret), his intentions were made clear in speeches and in the empowerment of his subordinates to act with deadly resolve.

Ghettoization and Mass Shootings:

The first stage of the Final Solution was the ghettoization of Jews, especially in occupied Poland. Starting in late 1939 and 1940, Nazis herded Jews into cramped, sealed-off ghettos in cities like Warsaw, Łódź, Kraków and many others. Conditions were horrendous – overcrowding, starvation rations, disease. The idea was to isolate and weaken the Jewish population further, and many tens of thousands died in ghettos from malnutrition and illness. But at this point, the ultimate plan for those in the ghettos was still being debated among Nazis: expulsion beyond the Urals after conquering the USSR? Prolonged enslavement? The answer soon tilted toward outright killing.

June 1941: Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. With it came Einsatzgruppen – special SS mobile killing units sent in behind the German army lines. Their orders: to shoot “enemies of the Reich” in newly captured territories, which very much included Jews (particularly Jewish men at first, but soon women and children too). The Holocaust by bullets had begun. These units, often aided by local collaborators and German Order Police battalions, shot hundreds of thousands of Jews in mass graves across Ukraine, the Baltics, and Russia in 1941-1942. Entire communities were marched out, forced to dig pits, and then gunned down. Babi Yar, near Kyiv, is one infamous massacre site: in September 1941, over 33,000 Jewish men, women, and children were shot over two days. Hitler was aware and approving of these massacres. In fact, Hitler’s anti-Jewish orders intensified with the war’s progression, especially after he blamed the Jews for inspiring Soviet resistance and American opposition (in his twisted logic, “world Jewry” stood behind the Allies).

However, shooting huge numbers of people had its “problems” (from the Nazi perspective): it was psychologically taxing for some of the killers, it was public (witnessed by locals), and it was inefficient for the total number of Jews the Nazis now controlled. So the regime looked for more “practical” methods – and found them in gas.

The Extermination Camps and Industrialized Murder:

By late 1941, the Nazi leadership made a fateful decision: to implement a “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”, which meant the systematic, planned annihilation of all Jews within their grasp. On January 20, 1942, top Nazi officials met at the Wannsee Conference near Berlin to coordinate this Final Solution. Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann outlined plans to deport Jews to “the East” and work them to death or outright kill them, and enumerated 11 million Jews in Europe as targets (even including Jews in neutral or enemy countries they hadn’t conquered – an aspirational genocide beyond their current reach). While Hitler was not at this meeting, it’s understood he authorized this direction – Himmler, Heydrich, and others took their cues from Hitler’s will, and he had repeatedly expressed that the war would entail wiping out Jews. Hitler received regular reports on the progress of the extermination (though couched in euphemisms) and never wavered in pushing it.

Thus began the deadliest phase of the Holocaust. Killing centers were established, especially in occupied Poland, solely for mass murder. Camps like Chelmno, Bełżec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek, and the infamous Auschwitz-Birkenau became factories of death. Here, Jews from all over Europe were transported in cattle cars: men, women, children, the elderly – no one was exempt. On arrival, most were told they were going for a “shower” to delouse; in reality, they were herded into gas chambers and asphyxiated with carbon monoxide or Zyklon B poison gas. Their bodies were burned in crematoria or buried in mass graves. Auschwitz, the largest, could kill up to 6,000 people a day in its gas chambers at the height of operations. By war’s end, approximately six million Jews had been murdered across Europe – roughly two-thirds of Europe’s pre-war Jewish population. This included over 90% of Poland’s Jews, about 2/3 of the Soviet Union’s, and significant portions from other countries.

It is critical to underscore Hitler’s central role in this genocide. While he delegated much, he set the ideological imperative and gave broad orders that drove the genocide forward. There is evidence Hitler was kept informed: for example, Heinrich Himmler (SS Reichsführer overseeing the genocide) met with Hitler regularly and noted in appointment books things like a discussion on the “Jewish question.” In December 1942, Himmler gave a speech to SS officers explicitly referencing Hitler’s 1939 prophecy and boasting it was being fulfilled “today” – a rare explicit admission of genocide framed as carrying out the Führer’s vision.

Hitler’s obsession with destroying Jews even overrode some military considerations. As the war turned against Germany, resources were desperately needed at the fronts, yet the trains to Auschwitz kept running and SS units continued hunting Jews instead of fighting soldiers. In the last months, with Germany in ruins, Hitler ranted about Jews in his will and final Testament, still blaming them for the war. This fanatical focus suggests that for Hitler, the extermination of Jews was not just a side effect of war, but one of his primary objectives. In his mind, he was “solving” what he saw as a cosmic problem. Indeed, Joseph Goebbels wrote in 1943 that the “European Jewish question” was being solved in a way that would be “a milestone in history,” indicating they all understood the grand, horrific scale of what they did.

The Final Solution was shrouded in secrecy. The Nazis used euphemisms like “special treatment” or “resettlement” for killing. Victims were often deceived up to the last moments. The world at large only gradually learned the full extent, and even some victims couldn’t believe what was happening until it was upon them – it was so extreme as to defy imagination.

For our purposes, however, it is the ultimate demonstration of where Hitler’s hatred led. What began as prejudice grew into discriminatory laws, then into violence, and finally into a program of total annihilation. The psychological groundwork – seeing Jews as subhuman, blaming them for everything – was essential for ordinary men to operate gas chambers and firing squads without collapsing. Many killers explicitly invoked Nazi propaganda; for instance, one Einsatzgruppen report justified slaughtering Jewish children by saying “in the children, see the grown-ups – if they were allowed to grow up.” This chilling quote reflects the deep internalization of the idea that Jews were a perpetual threat down to the last infant.

Thus, the Holocaust – the genocide of the Jews – stands as the ghastly fulfillment of Hitler’s hate. It is arguably the most fully realized genocide in history in terms of ideological driving force, bureaucratic planning, and industrial method. About 6,000,000 Jews were murdered, as well as millions of other victims (including Roma, disabled persons, Poles, Soviet POWs, etc. – though those groups were targeted for different reasons, and only the Jews were slated for total eradication everywhere). It’s critical to note: had Hitler not specifically hated Jews so intensely, the Holocaust would not have happened. Anti-Jewish prejudice long existed, but Hitler’s particular fanatical twist and the power he wielded were the lethal combination.

Hitler’s hatred became genocide – that is the stark answer to what his antisemitism meant in practice. It started as poisonous ideas and ended in gas chambers. Every step of the way, Hitler either initiated or encouraged the escalation. His inferiors often radicalized policies on the ground, but always in line with what they knew the Führer wanted. For example, local commanders might initiate killings even before formal orders, knowing Hitler’s desires. And indeed, Hitler never punished any official for being too harsh to Jews – only for being too soft.

By the end of World War II in 1945, this obsession had come full circle. Hitler, hiding in his bunker as Berlin fell, raved that the Jews had finally been defeated – as if the extermination was an accomplishment amid Germany’s ruins. It’s a bitter irony: Hitler’s war of annihilation brought untold suffering to the world and even destroyed Germany, yet he considered the murder of Jews as some twisted triumph.

We have delved into the darkest chapter of Hitler’s hatred. It is difficult but necessary: This shocking fact still haunts history – one man’s rabid prejudices led to the industrialized slaughter of millions of innocents. We must remember that behind every statistic was a human life – an old rabbi, a young mother, a little boy or girl – extinguished because Hitler convinced the world they didn’t deserve to live.

Now, having recounted this grim history, we must grapple with the broader question: Why did Hitler hate the Jews so much? We’ve traced the how – psychological, political, historical factors – and the what – the destructive results. But was Hitler’s hatred purely ideological? Personal? Strategic? Delusional? In the next section, we’ll analyze the possible motivations and mindset behind Hitler’s antisemitism, to glean whether it was driven by personal experiences, cold political calculus, or outright paranoid delusion (or all of the above). Understanding this helps ensure we learn the right lessons from this tragedy.

The Psychology of Hatred – Personal, Strategic, or Delusional?

In this section, we analyze why Hitler’s antisemitism took the form it did. Was his hatred purely ideological and delusional, or did he use it strategically? We consider psychological factors: Hitler’s personal grievances, need for a scapegoat, and genuine belief in conspiracy theories. The goal is to understand what drove his obsession and whether it was calculated or deeply sincere (or both).

Why did Hitler hate the Jews with such intensity? It’s a question that has intrigued and horrified historians and psychologists alike. The simplest answer is: because he chose to. There was no rational reason – Jews in Germany were a tiny minority (less than 1% of the population in 1933) with disproportionate contributions to society in science, arts, business. They didn’t actually control Germany or cause its defeat. But Hitler’s mind was not guided by reason on this matter; it was governed by deep-seated prejudice, warped ideology, and perhaps personal psychological needs.

Personal Grievances and Early Influences: Unlike some antisemites, Hitler had no specific traumatic incident involving a Jew that turned him anti-Jewish. As noted, myths about a Jewish professor rejecting his art or a Jewish doctor harming his mother are false. In fact, Hitler’s early life included kind interactions with some Jews, which he later conveniently forgot or twisted. So, personal direct harm was not the driver. However, Hitler’s personal frustrations played a role. He was a failed artist, an aimless drifter, someone who felt entitled to greatness but languished in poverty. Psychologically, it’s common to search for external blame in such situations. Jews became, for Hitler, a scapegoat for his personal failure. As a young man in Vienna, seeing successful Jewish professionals or wealthy Jewish businessmen may have sparked envy. Hitler often accused Jews of profit-seeking and lacking idealism – complaints that sound like a resentful starving artist sneering at those more prosperous. This personal resentment likely blended into the general antisemitic climate he absorbed.

Moreover, Hitler had a grandiose personality – a need to see himself as heroic and Germany as glorious. The existence of any internal “enemy” provided a convenient villain for his life’s drama. It’s telling that Hitler’s antisemitism intensified exactly when he or Germany were humiliated (his Vienna destitution, Germany’s WWI defeat). In those dark moments, believing “the Jews betrayed us” was psychologically comforting – it externalized blame. A clinical psychologist might say Hitler projected his self-hate or weakness onto Jews. Some have speculated Hitler’s hatred had a pathological quality – almost obsession-compulsion. Indeed, he fixated on Jews irrationally, beyond what was politically expedient. Even when it hurt Germany (like diverting resources to kill Jews during war), he persisted, hinting at an inner compulsion.

Delusional Ideology – He Believed His Own Lies: Many historians conclude that Hitler genuinely believed much of the antisemitic conspiracy he propagated. He was, as one article put it, a “failed artist, delusional conspiracy theorist”. He lived in a bubble of paranoia where “International Jewry” was orchestrating world events. This is not unique to Hitler – conspiracy thinking was rampant in his day (and sadly still is). But Hitler’s fervor and charisma spread his personal delusions to millions. It appears Hitler saw Jews not as individuals but as an almost metaphysical force of evil – in Mein Kampf he even described the Jew as the “devil” that lures nations to doom. This quasi-religious, apocalyptic view suggests delusion. He was not content to dislike Jews for normal prejudiced reasons; he had a whole fantasy of a global Jewish plot. Even toward the end, he ranted that Jews had caused the war to destroy Aryans, and thus Aryans had a duty to destroy Jews. It’s chilling how he framed genocide as self-defense – a sign of true paranoia.

Some biographers argue Hitler’s antisemitism became a fixed idée fixe – a single idea guiding all his actions. By believing Jews were behind both capitalism and communism, he could rationalize war against Western democracies and the Soviet Union as part of one grand fight. In Hitler’s twisted psyche, Jews were an omnipresent enemy that had to be exterminated for the world to be healthy. This is clearly irrational and delusional. It’s also why normal appeals (like Jewish WWI veterans’ patriotism or Jewish contributions to German culture) meant nothing to him. Facts didn’t matter, only the paranoid narrative. That’s why we call his hatred ideological: it wasn’t responsive to real behavior of Jews; it was a predetermined dogma seeking evidence to support itself.

Strategic Scapegoating – Hate as a Political Tool: While Hitler’s antisemitism was deeply felt, he also exploited it shrewdly. Politically, blaming Jews was incredibly useful in interwar Germany. As we’ve covered, post-WWI Germany was in crisis – hyperinflation, political violence, the shame of Versailles. Hitler offered Germans a simple explanation: the Jews did this to us, and a simple solution: remove the Jews and Germany will be great again. This scapegoating resonated. Many Germans who weren’t inherently murderous antisemites still went along because it was easier to blame a minority than to face messy truths (like the fact that WWI was lost due to military defeat and internal exhaustion). So, Hitler found antisemitism to be a great unifier and motivator for his base. It tapped into existing prejudices and bound his followers in a mission. Historian Lucy Dawidowicz wrote that Hitler used the Jews as a “whetstone” to sharpen his movement’s radical edge. From the Beer Hall speeches of early 20s to the fever-pitch rallies of the 30s, attacking Jews reliably whipped up the crowd.

In that sense, Hitler’s hatred had a cynical utility. Some wonder: did Hitler really believe all of it, or was he exaggerating for effect? Likely both. He seemed to truly believe it, but he also emphasized and performed it when politically advantageous. For example, during early diplomatic dealings (before WWII), Hitler sometimes toned down antisemitism if it was inconvenient (like hiding the worst actions during the 1936 Olympics to avoid scandal). That shows he could be tactically flexible, suggesting he knew when to fan the flames and when to briefly dampen them for strategy. But once war removed constraints, he unleashed the full measure.

Narcissism and the Need for an Enemy: Psychologically, Hitler was extremely narcissistic. He saw himself as a genius destined to save Germany. Narcissists often need an external enemy or obstacle to blame for their problems; it preserves their self-image of perfection. For Hitler, the idea of Jewish “poison” ruining everything provided a constant justification – if something went wrong, it wasn’t his fault, it was Jewish sabotage. It validated his worldview of being the heroic savior fighting a demonic foe. Without Jews, there would always be chance Hitler’s claims of German superiority could be undermined by real-world problems; with Jews as an omnipresent scapegoat, any failure could be spun as due to enemy action. This psychological crutch kept his ego intact. Notably, even in his final testament, Hitler blamed Jews for the war and almost took satisfaction that he had tried to destroy them – he couldn’t admit any failings, it was all the Jews’ doing.