"Adolf Hitler: From Homeless Artist to Tyrant – The Shocking Rise of a Dictator"

"Explore Adolf Hitler's transformation from a destitute artist to one of history's most infamous dictators. This in-depth analysis uncovers the psychological and societal factors that fueled his ascent to power."

Who Was Adolf Hitler: From Homeless to Monster, From Obscurity to Power

Troubled Youth in Austria and Homeless Struggles

Adolf Hitler was born in 1889 into a harsh household in Braunau am Inn, Austria. His father, Alois, was a strict and often violent customs officer, while his mother, Klara, was loving and protective. Hitler was a dreamy, poor student who did well only in history and art. When Alois died in 1903 and Klara later succumbed to cancer in 1907, young Adolf was left alone and grieving. He moved to Vienna at 18 to pursue art, but the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts twice rejected him. Penniless, he scraped by painting postcards and sleeping in cheap hostels. By late 1909 he was literally homeless on the streets of Vienna.

A watercolor landscape painted by Adolf Hitler during his early years, reflecting the peaceful aspirations of a young artist. In reality, Hitler’s Vienna days were marked by poverty: he sold postcards and lived in homeless shelters when funds ran out. During these bleak years he developed deep resentments. Surrounded by anti-Semitic politics in Vienna (the mayor, Karl Lueger, was virulently anti-Jewish), Hitler later claimed this period “began” his hatred toward Jews. In those quarters he met people like August Kubizek, who recalled the moody young man pacing flophouses and ranting about politics.

Hitler’s early life planted seeds of anger and ambition. An aloof loner with poor health and few friends, he was described by historian Laurence Rees as “a nobody, an oddball” with social awkwardness. He clung to Catholic roots but turned to political mythmaking to explain his country’s fate. By the time he left Vienna for Munich in 1913 (to avoid Austrian military service), Hitler was an embittered young man with artistic dreams shattered and a new fanatical worldview brewing.

World War I and the “Stab-in-the-Back” Myth

When World War I broke out in August 1914, Hitler eagerly volunteered for the German army. He found purpose and camaraderie that had been missing from his life. As a “trench runner” on the brutal Western Front, Hitler repeatedly braved no-man’s-land to deliver messages. He was wounded several times and earned the Iron Cross for bravery. The discipline and danger of war fulfilled him—and he became intensely German in identity, having renounced his Austrian citizenship in 1913.

War changed Hitler. He returned from the front broken by Germany’s defeat. Like many soldiers, he believed the army had been undefeated in the field and only betrayed by politicians at home. Hitler later wrote that the Army had been “stabbed in the back” by leftists and Jews who signed the armistice. Devastated by 1918, Hitler was obsessed with this conspiracy. His war years had also hardened his worldview: the chaos of trenches and defeat strengthened his fervent nationalism and anti-Semitism. After the armistice Hitler refused to let go of the notion that Jewish politicians and Marxists caused Germany’s collapse. He swore that Germany’s “November Criminals” must be removed from power.

Entering Politics: The Nazi Party and the Beer Hall Putsch

In 1919 Hitler was still a lowly army lance corporal, assigned to a unit that spied on political groups. He was sent to observe a tiny Munich group called the German Workers’ Party (DAP). Instead, he was captivated by their meetings and firebrand speeches. Within weeks Hitler quit the army and joined the DAP. Over the next year he won attention with impassioned oratory, becoming the party’s undisputed leader by 1921. Observers noted Hitler’s unique style: he spoke softly at first, then roared until audiences were spellbound. Writer Victor Klemperer captured the uncanny effect of Hitler’s speaking:

“I have never been able to understand how Hitler was capable – with his unmelodious and raucous voice, with his crude sentences, and with a rhetoric entirely at odds with the character of the German language – of winning over the masses with his speeches...”.

In other words, Hitler had no classical eloquence or military glory to boast. Yet his fiery hatred for Germany’s enemies (communists, Jews, liberals) struck a chord with defeated veterans and nationalists. As historian Laurence Rees explains, Hitler’s message “chimed with the feelings of thousands of Germans who felt humiliated by the terms of the Versailles Treaty”. One witness recalled: “The man gave off such a charisma that people believed whatever he said.” In beer halls and rallies, Hitler’s raw emotion and promises of redemption drew crowds hungry for meaning.

By 1923 Hitler had remodeled the DAP into the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP or Nazi Party). Confident of popular support, he recklessly attempted a coup in Munich that November. The Beer Hall Putsch was a fiasco. Armed Nazis marched on a Bavarian government meeting but were cut down by police fire. Hitler himself was arrested and charged with treason. In court (early 1924) he turned the tables: the trial became a national platform for his ideology. He was convicted but served only nine months in Landsberg prison. While jailed, Hitler dictated the first volume of Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”), a sprawling manifesto combining autobiography with his political, racial and expansionist theories. There he spelled out the Aryan ideology that would govern Nazi rule: Germans were a “master race” battling “parasites” and seeking Lebensraum (living space) in the East. As Britannica notes, Hitler called for a sacred mission to preserve Aryan purity, declaring “All who are not of a good race are chaff,” and writing that the elimination of Jews “must necessarily be a bloody process”.

Weimar Crisis and the Path to Power

In the mid-1920s, the Nazi Party lay mostly low. Hitler recovered his health and shrewdly reorganized the movement, emphasizing propaganda and mass rallies. However, it was the crises of the Weimar Republic that catapulted him. Germany in 1919 had been handed a humiliating peace: the Treaty of Versailles imposed crushing penalties. As one historian observes, Versailles was a “dictated peace” that split the German Empire, carved the army ‘to the bone,’ and demanded huge reparations. Germany was forced to pay $31.5 billion by 1921. The new republic staggered under economic chaos: Weimar struggled with debt, strikes, and inflation. These burdens bred deep resentment. Many Germans, including Hitler, blamed Versailles and declared Germany owed nothing.

The late 1920s saw some recovery, but the Great Depression changed everything. In 1929 a global economic collapse devastated Germany. Millions lost jobs and savings. The Weimar government alternated emergency decrees. As ThoughtCo historian Michael Johnston notes, “Hitler may not have taken power without the massive economic depression” of this era. With anger and fear spreading, Nazi promises of jobs, national pride, and scapegoats became irresistibly appealing. The Nazis painted Jews, communists, and the Versailles Treaty itself as villains.

Meanwhile, the Nazi party was skillfully exploiting elections. In the July 1930 Reichstag vote, the Nazis won 107 seats (up from 12 seats in 1928). By July 1932 they became the largest party in parliament with 230 seats. The once-obscure fringe was now mainstream. President Paul von Hindenburg, a World War I hero himself, dismissed the centrist governments. Under pressure, Hindenburg reluctantly appointed Hitler as Chancellor on January 30, 1933. This was a pivotal moment: a legally elected chancellor, steeped in dictatorship ideology, now stood at the head of government in Berlin.

Reichstag Fire to Enabling Act: The Nazi Coup

Once in office, Hitler moved quickly to seize complete power. On February 27, 1933, the Reichstag (parliament) building was set ablaze under mysterious circumstances. Hitler blamed communist agitators and used the Reichstag Fire as a pretext. The very next day he convinced Hindenburg to sign the “Decree for the Protection of People and State.” This emergency decree suspended constitutional rights — censorship of the press, mass arrests without due process, and the right to assembly were all voided. Within weeks the Nazis arrested thousands of Communists and Socialists across Germany.

With opposition muzzled, Hitler brought the Reichstag back and pushed through the Enabling Act on March 23, 1933. This law allowed his cabinet to enact laws without parliament. In effect, it legalized Hitler’s dictatorship. Over the next year he dismantled every check on power. Political parties (except the Nazi Party) were outlawed; state governors were replaced by Nazi loyalists; labor unions were banned. By mid-1934, Hitler ruled unopposed. Following President Hindenburg’s death in August 1934, he merged the presidency with the chancellorship and declared himself Führer — “Leader” of the Reich. From homeless drifter to sole ruler of Germany, Hitler had attained absolute power through a combination of violent terror, political maneuvering, and legal subterfuge.

Nazi Ideology and Society Under Hitler

With power consolidated, Hitler set about transforming Germany according to National Socialist doctrine. A cult of personality grew around him: his image was everywhere, from classrooms to temples of architecture. Nazi propaganda (masterminded by Joseph Goebbels) glorified Hitler as the savior of the nation. Meanwhile, the regime implemented radical, racist policies. Antisemitism was official state policy. Jews were progressively stripped of rights by laws like the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. Nazi textbooks taught Aryan supremacy; doctors and bureaucrats enforced eugenics programs to purge society of “undesirables.” Concentration camps were opened in the 1930s to imprison political opponents, the disabled, Romani, gays, and anyone deemed enemies of the regime. Hitler’s worldview was unapologetically brutal. He had idolized ideas in Mein Kampf and now acted on them. His speeches never hesitated to vilify communists, Jews, and the Allies, and to call for revenge. As AlphaHistory describes, Hitler despised non-Aryans, seeing them as Untermensch (“subhumans”), and aimed to build a “Greater Germany” by seizing living space in the East. He envisioned overturning Versailles and eradicating Germany’s perceived enemies.

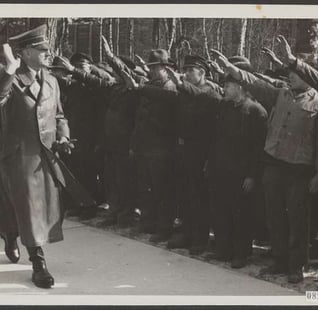

Despite the terror, Hitler’s early rule brought some popular satisfaction. He rebuilt the military in violation of Versailles, created jobs through massive public works, and reclaimed lost territories (the remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936, the Anschluss with Austria in 1938, the annexation of Sudetenland). Germans proud and hopeful flocked to Nazi rallies. But beneath the propaganda façade lay brutality: the Gestapo instilled fear, and any dissent was crushed.

Outbreak of World War II and the Holocaust

Hitler’s expansionism soon plunged Europe into war. On September 1, 1939, German tanks and planes thundered into Poland under the pretense of regaining “Lebensraum.” This blitzkrieg invasion, immortalized by images of burning cities, ignited World War II. In Warsaw after the attack, a charred Polish tank stands as a grim symbol of Hitler’s campaign (1939). Britain and France declared war on Germany days later. Hitler’s strategy was ruthless: he ordered the German army and SS to treat Polish civilians as enemy combatants, foreshadowing the monstrous violence of the coming years.

Hitler’s victories at first were swift. By mid-1940, Nazi forces had overrun Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and crushed France. In June 1941 he launched Operation Barbarossa, the massive invasion of the Soviet Union. Millions of Soviet troops and civilians died in the ferocious fighting. In tandem with the war, the regime enacted genocide on an unprecedented scale. What Hitler had advocated in theory now happened in atrocity: the systematic murder of Jews and other groups in the Final Solution. Entire Jewish communities across occupied Europe were gathered into ghettos and then sent to death camps such as Auschwitz and Treblinka. By 1945 an estimated six million Jews had been murdered alongside millions of Romani, Polish and Soviet civilians, disabled people, and others deemed Untermensch. Under Hitler’s racist vision, camps and mobile killing squads became instruments of industrial-scale slaughter.

Hitler was the architect of these crimes. As the Allies slowly turned the tide, he only grew more desperate. By late 1942 the German advance in Russia stalled (Stalingrad) and the Allies landed in Italy and France. Bombers reached German cities. Still, Hitler insisted on brutal last stands, often refusing tactical withdrawals. His inner circle became a den of intrigue and despair. Many officers secretly opposed him, but any trace of conspiracy was ruthlessly exposed (the July 1944 plot to kill Hitler, for example). In the face of total war, Hitler retreated into isolation in his Berlin bunker. There he married longtime partner Eva Braun and refused to accept defeat.

Defeat and Final Days

By early 1945 it was clear Germany would lose. Soviet armies crushed the Eastern Front, and on April 25 the Allies crossed the Rhine. On April 29, Hitler married Eva Braun in the underground Führerbunker beneath Berlin. The very next day, facing certain capture by Soviet forces, they committed suicide (he by gunshot, she by cyanide). Hitler’s body was burned in the garden outside the bunker, denying his followers a shrine.

The Third Reich crumbled. On May 7, 1945, Germany unconditionally surrendered. Six years after igniting a global war, Hitler was dead — his vision in ruins. The death toll of WWII was unprecedented: about 19 million soldiers and civilians from all sides perished under Hitler’s aggression. Historian Ian Kershaw calls Hitler “the embodiment of modern political evil,” responsible for the Holocaust and the war’s horrific casualties. The image of Hitler—once a penniless artist, now a demonic figure—haunts history.

Psychological and Social Forces Behind the Rise

What allowed a fringe agitator to become such a monster? Hitler’s life inspires deep analysis of personal and societal factors. Psychologists and historians note that Hitler combined charisma with conviction. He portrayed himself as a prophet of a national revival. As a young man he felt destined for greatness; he believed he was guided by “providence” and had a quasi-religious mission. His oratory played to emotion: he framed his personal failures (like his stammer, his shy manner) as signs of unique greatness. Many Germans, primed by defeat and desperation, were receptive. The public’s longing for stability and pride was a fertile ground for Hitler’s promises. As BBC historian Laurence Rees notes, Hitler exploited the zeitgeist: he spoke in a tone of mystic destiny that energized the beaten-down masses.

Hitler’s psychology was also marked by extremes. He was intensely neurotic and suspicious. His inner circle became echo chambers for his paranoid fears. By 1945 he was reportedly addicted to amphetamines and sedatives (to maintain his furious pace), which may have exacerbated his delusions of grandeur. Some psychiatrists have speculated about mental disorders, but no consensus exists. Crucially, Hitler was not clinically insane in the sense of psychosis; he remained a calculating ideologue with a clear (albeit twisted) vision. As Hannah Arendt later remarked, genocide can occur without the perpetrator being “mad” in a medical sense. Hitler’s cruelty was a choice within a murderous ideology, not merely pathology.

Socially, Hitler’s rise was enabled by chaos. The Weimar Republic was young and weak, battered by Versailles and class conflict. The Great Depression collapsed its economy, making even moderate solutions seem inadequate. Communists and monarchists were fierce rivals, so conservative elites on the right thought they could use Hitler to crush leftists. Even the generals and Hindenburg naively believed they could contain him. In this vacuum of effective leadership, Hitler’s single-mindedness looked like decisive strength. Propaganda and youth indoctrination extinguished dissent: the Hitler Youth and Nazi organizations turned impressionable Germans into loyal followers.

Hitler also tapped into longstanding prejudices. He used age-old antisemitic myths (Jews as scapegoats for financial woes, the “stab-in-the-back” Jews-blamed narrative). He blamed intellectuals and foreigners for Germany’s plight. In a sense, Hitler personified the collective rage of a wounded nation. He offered simple answers (“Germany first,” “purity of blood,” “lebensraum”) to complex problems. This demagogic appeal fulfilled sociologist Max Weber’s notion of a charismatic leader: Hitler’s authority rested on perceived extraordinary qualities and promises, rather than reasoned policy.

In summary, Hitler’s transformation was the result of both an unstable society and his own monstrous conviction. He was not a relatable hero or a born high priest of evil; rather, he emerged as a product of his times and personality. Everyday grievances were magnified by his ferocious ideology. His story is a reminder that during crises, the vacuum of leadership can be filled by charisma clothed in fanaticism.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Adolf Hitler died in 1945, but his impact endures. His life remains a chilling case study in how democracy can collapse from within. In the decades since, historians and the public keep returning to Hitler’s story to ask how it could happen. The answer lies in the details: a man made monstrous by cruelty, charisma, and circumstance.

Today, Hitler is universally reviled. In Germany, Mein Kampf remained under tight control for decades; only recently has annotated editions appeared for scholarly study. Globally, Hitler’s name is shorthand for evil and tyranny. His life warns of the dangers of fascism, unchecked nationalism, and hatred.

Key Takeaways:

Hitler’s rise was not inevitable but contingent on historic failures: punitive peace terms (Versailles), economic collapse, and weak government. He exploited each crisis with dramatic flair.

He was a master of propaganda and oratory: despite a gruff voice and mediocre education, he mesmerized crowds, as contemporaries observed.

Hitler’s ideology fused pseudo-science and myth. In Mein Kampf he deified the Aryan race and demonized Jews and Slavs, laying groundwork for genocide.

His dictatorship was consolidated legally and violently: the Reichstag Fire Decree and Enabling Act of 1933 gave him near-legal power, and purges like the 1934 “Night of the Long Knives” eliminated rivals.

The human cost of his rule was staggering: roughly six million Jews and millions of others were murdered under his regime, and WWII (which he started) caused tens of millions of deaths.

Hitler’s life is a dark lesson: it shows how a disillusioned, embittered individual can become an agent of catastrophe when society falters. As Winston Churchill warned, “Those that fail to learn history’s lessons are condemned to repeat them.” By studying Hitler’s path — from destitute artist to dictator — we remember the fragility of civilization and the necessity of vigilance against tyranny.

Sources: Historic biographies and scholarly accounts, including AlphaHistory, BBC History, Encyclopædia Britannica, Holocaust Encyclopedia, and contemporary historians, are cited throughout to provide evidence for this narrative. These sources ensure a factual and comprehensive portrait of Hitler’s life and rise.