Battle of the Bulge: An In-Depth Strategic and Human Analysis of WWII’s Ardennes Offensive

Explore the Battle of the Bulge from strategic planning and battlefield tactics to firsthand soldier and civilian experiences. This comprehensive analysis covers the December 1944 Ardennes offensive’s background, key engagements (St. Vith, Bastogne, Elsenborn Ridge, etc.), weather impacts, counterattacks, and its profound consequences in World War II

Background and Strategic Context (Late 1944)

By late 1944, Allied forces had broken out of Normandy and advanced rapidly across France. However, this success created severe logistical strains: supply lines were overextended and deep-water ports scarce. The Allies did capture Antwerp in early September 1944, but its port facilities were not operational until 28 November. This forced General Eisenhower and his command to make hard choices. With the decisive push into Germany delayed by shortages of fuel and ammunition, Eisenhower elected to hold the Ardennes sector lightly. The rugged Ardennes forest offered naturally strong defensive terrain and no immediate Allied offensive goals, so it was deemed a quiet “rest sector” for fresh or rebuilding units. In fact, Eisenhower’s own staff noted that the Ardennes could be held “by as few troops as possible” precisely because German forces were using that region as a diversionary cover story.

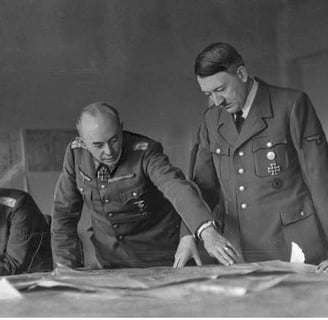

Behind the scenes, Hitler saw Germany’s war position as desperate after the failed July 20 assassination and relentless Soviet advance from the East. He was determined to launch one last offensive in the West to force a political settlement. The Ardennes was chosen because it was weakly held, remote, and well-concealed by dense woods and December fog. German planners gathered roughly 200,000 men, nearly 1,000 tanks (including elite Waffen-SS panzer divisions), and extensive artillery for Unternehmen „Wacht am Rhein“ (Operation Watch on the Rhine) to break through the Allied lines, drive to the port of Antwerp, and split the American and British armies. Seizing Antwerp would cut off Allied supply and perhaps enable Hitler to negotiate for peace from a position of strength. To ensure surprise, the Germans timed the attack for winter conditions: heavy fog and snow would ground Allied air power, just as hoped.

Allied commanders were not fully prepared. In December 1944 only four American divisions (two battle-hardened but depleted from fighting in the Hürtgen Forest, and two inexperienced replacements) defended an 80–90 mile front through the Ardennes. Moreover, Ultra intelligence warnings about German buildups in the Ardennes were dismissed; senior Allies assumed the Germans were massing for defense, not offense. Thus, when the Germans struck, the Allies were initially caught off-guard.

German Offensive Plan and Initial Assault (16–18 December 1944)

On the morning of December 16, 1944, the German counterattack erupted. Preceded by a massive artillery bombardment, three German army groups punched into the thin Allied front. The misty morning and forest cover blinded American observers. According to U.S. Army records, “more than 200,000 German troops and nearly 1,000 tanks” launched Hitler’s last gamble that day. German forces immediately broke through, encircling an American infantry division and seizing key crossroads toward the Meuse River. The crinkled “bulge” in the Allied line had begun.

The surprise was staggering. Reports of Nazi atrocities spread fear: the Malmedy and Stavelot massacres (where Waffen-SS troops murdered dozens of unarmed American POWs) were widely known almost instantly. German commando teams also infiltrated allied lines by speaking English or wearing captured uniforms, capturing bridges and cutting communications. Belgian civilians recalling 1940 frantically replaced Allied flags with swastikas, and allied troops braced themselves for a crisis.

American soldiers were thrust immediately into fierce combat under bitter winter weather. Historian Martin King notes that tanks and infantrymen of the 82nd Airborne and other divisions “pushed through the snow” and that Allied outposts in the Ardennes had long been assumed safe “honeymoon sectors”. The opening hours saw German Nebelwerfer rockets—nicknamed “screaming meemies”—hiss through the pea-soup fog and devastating barrages of artillery pound the front lines. By nightfall on Dec 16, German columns had driven 10–20 miles west, creating the salient which gave the battle its name.

Many American units were surrounded or overrun. Two regiments (around 8,000 men) of the 106th Infantry Division were cut off in the northeast Ardennes and forced to surrender on December 19. This was the largest single surrender of U.S. troops in the war. Meanwhile, in other sectors terrified GIs and civilians faced bombardment and infiltration. One British intelligence report noted that German combat engineer teams – some speaking perfect English – were conducting raids behind Allied lines.

Key Engagements: December 1944

St. Vith and the Elsenborn Ridge

In the northern Ardennes, U.S. forces were surprised and pushed back toward the Elsenborn Ridge, a series of hills with key road junctions. The 7th Armored, 106th Infantry, 9th Armored, and 28th Infantry Divisions were quickly thrown into combat to slow the advance. Elements of the 7th Armored Division moved to hold the town of St. Vith – a critical rail and road hub – against the northern thrust. As veteran John Jamele recalled, “the 7th (along with elements of the 106th, 28th, and 9th Armored Divisions) absorbed much of the weight of the German drive, throwing the German timetable into great disarray”. In freezing fog and deep snow, Americans dug in on Elsenborn Ridge and fiercely defended crossings over the Ourthe River. Constant German assaults from December 17–23, involving the veteran 12th SS Panzer Division and 277th Volksgrenadiers, gradually yielded ground to the Germans, but at a heavy cost and much slower pace. The ridge’s defense would prove crucial to slowing the German northern attack.

Bastogne and the Ardennes “Corridor”

In the center of the offensive, the German 5th Panzer Army drove southwest toward the Belgian town of Bastogne, nestled between key roads. U.S. forces (primarily combat commands of the 10th Armored Division and elements of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions) moved to defend the Bastogne corridor. By the morning of December 22, German spearheads had encircled Bastogne, trapping roughly 20,000 men inside. The acting commander of the 101st Airborne, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, famously replied “Nuts!” to a German demand for surrender. In the below-freezing weather, the outnumbered Americans consolidated in the town and its perimeter: they entrenched along the Petit-Spay, long-range artillery shelters, and any available cover. Armor crews dug their Shermans into foxholes; infantrymen wearing snow capes patrolled wrecked streets.

Supply was critical. Aircraft eventually dropped ammunition and medical supplies into Bastogne. Isolated and under heavy shellfire, the defenders nonetheless repelled repeated German attacks. As the U.S. Army historian notes, “at the critical road junctions of St. Vith and Bastogne, American tankers and paratroopers fought off repeated attacks”. Bastogne’s garrison, including men of the 101st Airborne, 10th Armored, and 82nd Airborne, held firm under a literal winter siege. (A U.S. Army photo of engineers emerging from the woods near Bastogne shows how closely the fighting pressed into towns.)

On December 25, amid one of the worst Christmases on record, weather began to improve. Allied air support, which had been grounded by fog, started to operate again. Meanwhile, reinforcements and supplies began reaching the front. Crucially, elements of Patton’s Third Army turned north from the Saar Valley and raced toward Bastogne and St. Vith to relieve the siege. By December 26 the first Allied vehicles reached Bastogne’s perimeter, providing fresh ammunition and building confidence.

Fighting Through the Ardennes (Dec 26–31)

Through late December, heavy combat continued in cold snowdrifts. Germans pushed to widen the bulge. American infantry on the flanks fought delay actions in woods and villages. Thomas J. Krebs, a soldier in “L” Company of the 75th Infantry Division, described one daytime attack on December 25:

“We began the attack at daybreak crossing the frozen, snow-covered field. As we got about 50 yards out, all hell broke loose and the Jerries laid down a field of fire with machine guns… I could not visibly locate the enemy as they were pretty well concealed. […] We were all alone in this heavily wooded area with machine gun and small-arms fire whizzing over our heads… We kept on firing until our ammo ran out. The Jerries began to drop in mortar shells around us. We got out of there in a hurry.”

Such intensity typified the fighting. Small American units held woods and crossroads to block tanks. At Elsenborn Ridge, for example, the 99th and 2nd Infantry Divisions managed to contain several German counter-attacks (including panzers of the 12th SS Panzer) between December 17–23, inflicting heavy losses. One relief operation turned churches into battle sites: US troops entrenched in the stone church at Krinkelt (near Elsenborn) and were fired on at point-blank range by German Panthers. Throughout this period, the weather remained bitter. Troops on both sides endured frostbite and trench foot as they slogged through snow drifts. American records note that from Christmas through January 1945, “American troops, often wading through deep snow drifts, attacked the sides of the shrinking bulge”.

Meanwhile, the 7th and 28th Divisions continued to trade blows around St. Vith. The town itself changed hands several times by early January. Although ultimately the defenders had to withdraw by December 23, their stubborn defense north of Bastogne delayed German forces from reaching the Meuse River.

Firsthand Soldier Experiences

The Battle of the Bulge produced many harrowing firsthand accounts. Soldiers on the ground recount tactics and chaos in vivid detail. For instance, Private Ronald McArthur of the 45th Infantry Division described intense forest fighting on January 11, 1945:

“We set our guns up on the high ground. It was all quiet until about four o'clock when suddenly we were hit with a terrific artillery barrage… I left my gun to cut logs for our foxhole roof. Then WHAM – I was shot through the face by a German sniper… I fell in 15 inches of snow, numb and not sure if my tongue was gone. I remember thinking only, ‘When will he let me have it again?’”.

His story illustrates the extreme risk soldiers took even while fortifying positions. Similarly, Sergeant Lou Novotny of the 28th Infantry Division recalled the disorienting fog and narrow escapes:

“Visibility was heavy fog, only about 20 yards. Darkness fell, and I was tasked with laying barbed wire. I walked through the fog — I came upon the enemy out of the fog, thinking I was the enemy and be shot at. I heard German voices and realized I was twenty yards from a German machine gun. If I had made a sharp sound, I’d have been riddled. I slowly and quietly turned around and walked back safely to my platoon.”.

These accounts show the fear, improvisation, and courage of GIs under fire. Many soldiers later emphasized that no training could fully prepare a man for what they endured in the Ardennes. Nevertheless, time and again American infantry, tankers, and artillerymen found ways to delay superior German forces. They destroyed fuel stockpiles to keep them from German tanks, stubbornly held crossroads, and even quizzed unfamiliar-sounding soldiers with arcane American trivia to catch infiltrators.

Civilians Caught in the Crossfire

Not only soldiers suffered. Tens of thousands of Belgian and Luxembourg civilians lived under fire. Most conventional histories have largely overlooked them, but recent research documents civilian fate in grim detail. Historian Peter Schrijvers estimates that roughly 3,000 civilians were killed during the Battle of the Bulge – about one Belgian/Luxembourg person for every six American combatants killed. In other words, Ardennes townsfolk suffered as much terror from artillery and tank fire as Allied soldiers did from enemy guns.

As the fighting raged, civilians were initially caught between hurried evacuations and sudden attacks. Some had already fled months before; those who remained were trapped by January 1945. Schrijvers notes that German and American artillery often treated whole villages as targets. For example, in the twin villages of Krinkelt-Rocherath (north of Bastogne), American troops used the stone church as a fort; German Panther tanks replied with point-blank shells on the ancient walls. Under one shattered house in Rocherath, the Droesch family – father Johann, mother Maria, and daughter Hedwig – huddled through waves of combat. With German dead lying in the streets and houses burning, Hedwig later recalled how they cowered on “nothing left to eat… crying and praying” in the cellar.

The general feeling of helplessness is captured in a villager’s diary entry from Christmas Day 1944: “We feel like we are in God’s hand… and we surrender ourselves to it.” Schrijvers emphasizes that for civilians in the Ardennes, there was little choice but to flee or hide as fighting came to their doorstep. In many cases, families fled into basements together, listening to the “full fury of combat” overhead. Schrijvers writes that “if a village had been or was the scene of a battle, its civilian population was usually gone” – yet in the Ardennes thousands could not escape.

Despite this suffering, occupied towns often provided invaluable aid to Allied troops. When U.S. units advanced, local Belgians frequently guided them along mountain paths or even handed over vehicles and horses. Sometimes the Allies were met with cheers. In Liège in September, for example, civilians were said to have climbed onto the tanks of the 3rd Armored and begged for arms. (By contrast, retreating Germans saw towns as security threats; anyone remaining could be shot or arrested on suspicion of partisanship.) Ultimately the Ardennes marked the culmination of nearly a year of hardship for the local people – victims of bombing, scorched-earth tactics, and the bitter cold with little international attention.

Photo: U.S. infantrymen of the 7th Armored Division move cautiously through a snow-covered street in St. Vith, Belgium, on Christmas Day 1944. Soldiers dug in on winter camouflage and endured deep snow drifts throughout the Ardennes campaign. (Courtesy U.S. National Archives.)

Allied Counteroffensive (January 1945)

With the New Year came clear weather and renewed Allied action. By January 1, 1945 the fog lifted enough for Allied air forces to strike German columns, supply lines, and troop positions. The two Allied armies (First and Ninth) along the northern Bulge axis attacked south and east, while Patton’s Third Army (arriving from the south) pivoted northward. U.S. armored divisions advanced along both shoulders of the salient to cut it off.

One map from the period (see below) shows the Allied counteroffensive in early January 1945: American and British divisions pushing from east and west, sealing the bulge. Radio intercepts and coordination allowed the pincer movement. By mid-January the Germans were being squeezed out of the Ardennes and into crumbling defensive positions. On January 16, two small American patrols – one from the 84th Infantry Division and one from the 11th Armored Division – met on the Ourthe (Liourthe) River near Houffalize, Belgium. This historic link-up “unites two U.S. Armies and solidifies the front line,” effectively closing the German salient.

Image: U.S. Army map of the Allied counter-offensive in the Ardennes (January 3–28, 1945). This map (from the Official Army historical archives) illustrates how American and British forces advanced from north and south to pinch off the German “bulge,” eventually restoring the front to its pre-December configuration.

By the end of January the German offensive had been driven back to their starting lines. American units recaptured lost ground in Belgium and Luxembourg, and Bastogne was relieved on January 26 by elements of Patton’s army. The last German remnants withdrew across the rivers and into the Siegfried Line fortifications. As U.S. Army historians note, “through January, American troops… attacked the sides of the shrinking bulge until they had restored the front and set the stage for the final drive to victory.”.

Photo: In mid-January 1945, two patrols – one from the 84th Infantry Division (First U.S. Army) and one from the 11th Armored Division (Third U.S. Army) – meet at a prearranged rendezvous on the Ourthe (Liourthe) River. This historic contact, on January 16, 1945, closed the bulge and reunited the American armies.

Casualties, Outcomes, and Legacy

The Battle of the Bulge was costly for both sides. Allied casualties numbered about 75,000 (including some 19,000 killed), while German casualties were roughly 120,000 (of which about a third were killed). For Germany these losses were irrecoverable. Strategically, the offensive failed in its objectives. The Allies retained Antwerp, their armies remained connected, and the Germans exhausted irreplaceable men and materiel. Most historians agree it was Hitler’s last realistic bid to turn the tide; after January 1945 Germany never again mounted a major offensive in the West.

Politically and symbolically, the Bulge had profound implications. Winston Churchill summed up its significance by declaring it “undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war,” a testament to U.S. troops’ tenacity under desperate conditions. In the United States and liberated Belgium, the battle became a symbol of resistance and resilience. It also shaped Allied high command decisions: the looming assault confirmed that an eastern advance into Germany should proceed on schedule (the Eastern Front was collapsing and Germany needed all its resources to halt the Soviets), while in the West the Rhine crossings would follow as quickly as possible.

For historians and military analysts, the Ardennes battle remains a case study in leadership, logistics, and combined arms in harsh winter terrain. It highlighted the perils of intelligence failure (Allied overconfidence in Ardennes quiet), the importance of air superiority (bad weather gave the Germans their initial edge), and the sheer determination of infantry facing armored assaults. Stories from the front – bastions like Bastogne, the “Nuts!” reply, the cold Christmas under siege – endure in World War II lore.

In terms of legacy, the Bulge reshaped Allied operations only in that it delayed final offensives by a few weeks. The armies regrouped and by March 1945 they crossed the Rhine. But the battle’s memory lives on in Europe (numerous monuments and cemeteries dot the Ardennes) and America (annual memorial services and cultural references). It stands as a reminder of the human cost of war and the endurance of soldiers and civilians alike under fire.

Timeline of Key Events

Dec 16, 1944 – German offensive begins. Over 200,000 German troops and ~1,000 tanks launch a surprise attack in fog. Allied lines are broken; Americans begin withdrawing to secondary positions.

Dec 17–19, 1944 – American units encircled, Malmedy massacre. Two regiments of the U.S. 106th Division (over 6,800 men) are surrounded and surrender by Dec 19. In the meanwhile, SS troops execute ~84 U.S. POWs near Malmedy, shocking the Allies.

Dec 19–23, 1944 – St. Vith & Elsenborn Ridge fighting. U.S. divisions (including 7th Armored) defend critical road junctions at St. Vith and the Elsenborn Ridge, delaying German spearheads toward the Meuse. Intense winter combat rages in woods and villages.

Dec 22–26, 1944 – Bastogne siege begins. The town of Bastogne is surrounded on Dec 22. Brig. Gen. McAuliffe’s 101st Airborne Division responds “Nuts!” to surrender demands. Harsh weather isolates the defenders, but Allied planes begin airdrops to sustain them on Christmas Day. By Dec 26, elements of Patton’s Third Army reach Bastogne’s perimeter.

Dec 25–31, 1944 – Weather clears; initial counterattacks. Fog lifts around Dec 23, allowing Allied air raids on German positions. U.S. and British forces on the flanks begin counterattacks. Americans drive Germans back toward their start lines in some areas.

Jan 1–15, 1945 – Allied counteroffensive accelerates. U.S. divisions press into the bulge from north and south. The Germans, low on fuel and ammunition, can no longer hold all gains. On Jan 16, two U.S. patrols meet on the Ourthe River (see photo above), linking the First and Third U.S. Armies and “closing” the bulge.

Jan 16–25, 1945 – Bulge collapse. Remaining German forces are pushed back or surrender. The siege of Bastogne is lifted on Jan 26. By Jan 25 the front is restored to roughly its pre-battle line. Hitler’s Ardennes offensive has failed.

Aftermath: The Allies, though battered (with ~75,000 casualties), prepare for the final assault into Germany. Germany (with ~120,000 casualties in the Bulge) is on the strategic defensive for the remainder of the war.

Sources: This article synthesizes official histories, eyewitness accounts, and recent scholarship on the Battle of the Bulge. All factual statements are cited.