The Byzantine Empire: How the Eastern Roman Empire Preserved and Shaped Western Civilization"

Discover the captivating history of the Byzantine Empire—the Eastern Roman legacy that preserved classical knowledge, influenced Christianity, and laid the foundation for modern Europe.

Introduction

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman state in its eastern provinces. Its history stretches from the founding of Constantinople by Emperor Constantine in 330 CE to the city’s conquest by the Ottomans in 1453 CE. In its own time, Byzantium saw itself as the Roman Empire reborn – inhabitants called themselves “Romans” and their emperor was the basileus tōn Rhōmaiōn (“Emperor of the Romans”). Yet over its millennium-long story the empire developed a distinct Greek-speaking culture, forging new artistic, legal and religious traditions that blended Greco-Roman heritage with Christian faith. It became medieval Europe’s longest-surviving state, and its legacy endures today in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Byzantine art and architecture, and the legal codes of many modern nations.

Timeline of Key Events:

330 CE: Emperor Constantine dedicates Byzantium (renamed Constantinople) as the new capital of the Roman Empire.

395 CE: Theodosius I’s death splits Rome permanently; the West falls to Germanic invasions, while the Eastern (Byzantine) Empire persists.

527–565 CE: Reign of Justinian I, who reconquers North Africa, Italy, and parts of Spain and codifies Roman law.

1054 CE: The Great Schism formalizes the break between the Western (Roman Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) Churches (see below).

1204 CE: The Fourth Crusade sacks Constantinople, creating a short-lived Latin Empire and scattering the Byzantine court.

1261 CE: Byzantines recapture Constantinople under the Palaiologos dynasty, but the empire is a shadow of its former self.

1453 CE: Ottoman forces under Mehmed II capture Constantinople on 29 May 1453, ending the Byzantine Empire.

This article explores the Byzantine Empire’s history and legacy: its political rise and fall, cultural achievements (art, law, architecture), military strategies, the spread of Orthodox Christianity, and how this Eastern Roman Empire shaped later world history.

Foundations: Constantinople and the Early Empire

The Byzantine story truly begins with Emperor Constantine I (ruled 306–337). In 330 CE he dedicated the city of Constantinople (“City of Constantine,” modern Istanbul) on the site of the old Greek colony Byzantium. Perched on the Bosporus Strait, its strategic harbors and defensible walls made Constantinople the natural new capital of a reunited Roman Empire. Shortly after Constantine, Christianity was legalized (312 CE) and then made the empire’s state religion, firmly anchoring Byzantine identity in the Christian faith.

After Theodosius I’s death in 395 CE, the empire formally split. The Western half quickly dissolved into Germanic kingdoms, but the Eastern Roman Empire endured. It retained the Roman governmental apparatus (an emperor with senate and bureaucracy) but gradually became more “Greek” in character. Greek was the common tongue, while Orthodox Christianity and classical Greek learning flourished in schools and churches. Defended by massive walls and led by quick-thinking emperors, Constantinople became medieval Christendom’s richest and most cosmopolitan city. (For example, under Theodosius II in the 5th century the famous Theodosian Walls were built to guard the city, and the great Hagia Sophia church was first constructed in 360 CE.)

Justinian I and the Golden Age

The mid-6th century was Byzantium’s Golden Age, ruled by Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). Ambitious and energetic, Justinian — often aided by his wife Empress Theodora — sought to restore the glory of Rome. His general Belisarius reconquered former Western provinces, retaking Carthage from the Vandals and northern Italy from the Ostrogoths. For a brief moment, the Byzantine state spanned the southern Mediterranean from Spain to Syria, as seen in the map below.

Map of the Eastern Roman Empire at its greatest extent under Justinian I (c. 565 CE).

Alongside his military campaigns, Justinian undertook sweeping reforms at home. In law, he commissioned the Corpus Juris Civilis (“Body of Civil Law”) — a codification of Roman legal tradition. This Justinian Code collected centuries of laws and edicts into an organized system. It clarified legal procedures and would influence European law for a millennium. Under Justinian’s patronage the capital also saw breathtaking building projects: chief among them the new Hagia Sophia (532–537 CE), a colossal domed cathedral that became the epitome of Byzantine architecture. (As Britannica notes, Hagia Sophia “changed the history of architecture” and remained the world’s largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years.)

Justinian’s reign was not without hardship. The empire was shaken by the Plague of Justinian (circa 541–542 CE), a devastating epidemic that struck Constantinople and beyond. Yet under Justinian Byzantium felt the thrill of its own revival: Roman law revived, ancient borders recaptured, and Christian civilization celebrated. Empress Theodora’s famous court mosaic (in Ravenna) offers a vivid glimpse of this era’s splendor.

Detail of a 6th-century mosaic of Empress Theodora (r. 527–548) in San Vitale, Ravenna. Theodora and Justinian (not shown) projected imperial grandeur through art and ceremony.

Justin ian’s legacy lived on long after his death in 565. Even as armies reconquered distant lands, new challenges arose on the empire’s frontiers.

Trials and Recovery: Invasions and Renewal

After Justinian’s conquests, Byzantium faced relentless pressures. In the 7th century, a newly unified Islamic Caliphate overran Byzantium’s eastern provinces. By 638 CE the Arabs had seized Syria, and Egypt fell soon after. Constantinople itself endured two massive Arab sieges (674–678 and 717–718) but held firm behind its walls. It was Byzantine naval tactics — most famously the use of Greek fire — and the determination of rulers like Emperor Leo III that saved the city. Greek fire was a secret incendiary weapon (a petroleum-based “flame-thrower” used from ships and walls) that burned even on water, utterly demoralizing besieging fleets.

Beyond the Arab threat, Byzantium grappled with internal conflicts and religious disputes. The Iconoclasm controversy (8th–9th c.), which saw two periods of icon burning and church division, tested the empire’s unity. Yet by the 9th century a cultural revival took hold under the Macedonian dynasty (starting with Basil I). Byzantine armies slowly regained strength. Leo VI and Basil II (the “Bulgar‑Slayer,” r. 976–1025) launched successful campaigns in the Balkans and against Arab forces. By 1025 the empire once again controlled wide swaths of Eastern Europe and Asia Minor (even incorporating fierce Varangian mercenaries from Rus’ into its armies). This period saw literature and learning flourish, as the court patronized scholars and architects alike.

Even as power ebbed and flowed, one thing remained constant: Byzantium’s military skill. Its armies were among medieval Eurasia’s most effective. The theme system (provincial armies settled on land for local defense) ensured a ready militia in every region. Over time, heavy cavalry (cataphract knights in lamellar armor) became the army’s backbone, replacing the old Roman legions. Byzantine generals excelled in diplomacy and cunning strategies as much as in open battle. For example, when Arabs first attacked Constantinople, Emperor Constantine IV famously diverted shipping by having fresh water dug to the city walls, depriving the enemy of wells. Such ingenuity, combined with Greek fire, repeatedly allowed Byzantine forces to punch above their weight against invaders.

Culture and Achievements

Byzantine civilization shone brightly in art, architecture and scholarship. The wealth of Constantinople and other cities funded the creation of stunning mosaics, lavish palaces and unique religious art. From the capital’s Great Palace to church interiors, gold tesserae glistened with saints and emperors. Byzantine artists fused classical realism with abstract, spiritual forms. Icon painting (sacred images) became a hallmark, representing Christ, Mary, and the saints in a stylized, timeless manner. These icons were venerated in churches and homes across the Orthodox world (and ignited fierce debate during Iconoclasm).

Interior of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (modern Istanbul). This 6th-century church, rebuilt by Justinian I, epitomizes Byzantine architecture with its soaring dome and luminous mosaics.

Architecturally, Byzantium synthesized Roman engineering and Eastern flair. Domed churches on pendentives (curved triangular supports) became the norm. The Hagia Sophia (above) remained the greatest example: its massive dome seems to float on a ring of light-filled windows, an “epitome of Byzantine architecture”. Inspired by such monuments, the empire built hundreds of smaller domed basilicas from Ravenna to Antioch, creating a distinct skyline of golden cupolas.

Education and learning also thrived (especially during the Macedonian Renaissance). Greek classics were copied in Byzantine scriptoria, preserving Plato, Aristotle and many Roman authors. Monasteries and patriarchal schools taught theology, philosophy and medicine. The emperor’s court itself promoted scholarship: famous figures like the historian Procopius and the architect Isidore of Miletus left enduring works.

Politically, Byzantium borrowed and innovated. The scholar-emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus wrote about administration, emphasizing ceremony and civil service. The Justinian Code (Justin ian’s legal compilation) remained the foundation of Byzantine law. In everyday life, Byzantines cherished family and tradition, yet the legal reforms allowed some social mobility and the rule of law rarely seen in the West during the Middle Ages.

Byzantine cultural influence extended far beyond its borders. As Britannica observes, the Eastern Church “not only enjoyed parallel expansion but also extended its missionary penetration… to Russia and the Caucasus”. In 988 CE, Kievan Rus’ adopted Orthodox Christianity and Byzantine rites, bringing the Cyrillic alphabet and Byzantine liturgy to Slavic lands. Orthodox faith and Byzantine art thus became the bedrock of countries like Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia. Even in Italy and Spain, former Byzantine territories, Greek scholars and artists left their mark on the early Renaissance. In the words of one historian, Byzantium’s culture was “influenced by the Greco-Roman tradition but also distinct,” a hybrid whose echoes survive in Eastern and Central Europe today.

Byzantine Military Tactics

The Byzantine military balanced tradition with innovation. Alongside its famed cavalry and navy, Byzantium excelled in tactical warfare. Armies often used ambushes, feigned retreats and intelligence-gathering to outmaneuver enemies. For example, during the 11th century Byzantine generals confronted Normans and Seljuks by choosing battlegrounds that neutralized cavalry charges, or by forming alliances with neighboring powers.

Greek fire (discussed above) was a strategic game-changer in naval warfare. Byzantine dromon galleys were equipped with bronze tubes that hurled this napalm-like liquid at enemy ships. At one celebrated moment in 673 CE, Byzantines repelled a vast Arab fleet by unleashing Greek fire under cover of darkness, setting hundreds of ships ablaze.

On land, the theme system decentralized defense: provinces (themes) were granted lands to local farmers-soldiers. This meant a quick-mobilizing militia could slow invasions. The core of Byzantine armies, however, was professional heavy cavalry. Clad in metal scales and riding couched-lance cataphracts, these mounted troops could break enemy lines in shock attacks. In prolonged campaigns, the Byzantine stratēgos (general) also used diplomacy – bribing foes or fomenting dissent among enemies – as a tactical tool.

Despite these strengths, Byzantine armies eventually declined. By the 11th century, defeats like the Battle of Manzikert (1071) against the Turks showed that outdated tactics could fail. Nevertheless, for most of its history the empire’s military tradition was formidable, a legacy of Roman discipline and Eastern ingenuity.

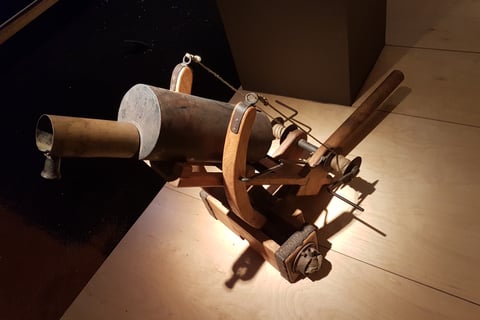

Reconstruction of a Byzantine Greek fire flamethrower (Thessaloniki Technology Museum). Incendiary weapons like this gave Byzantine fleets a deadly edge against besieging enemies.

Orthodox Christianity and the Church

A defining element of Byzantium was its Orthodox Christian faith. From Constantine onward, emperors saw themselves as God’s deputy on earth and guided the Church’s affairs. Grand councils (like Nicaea in 325 CE) were held in Constantinople or nearby, setting Christian doctrine that shaped both the empire and world Christianity. Over centuries, the Patriarch of Constantinople became one of Christendom’s most important religious figures. As one scholar notes, on the eve of the year 1000 “the church of Constantinople… was at the peak of its world influence and power”, surpassing Rome itself in prestige.

The Byzantine Church was also a vehicle of imperial policy. Emperors built monasteries and endowed clergy, while church leaders sanctified emperors. This symphony of Church and State (known as symphonia) differed from Western Europe’s model. Beyond politics, Byzantines produced influential theology, hymnography and icon painting. The liturgy of Hagia Sophia, with its incense, chants and columns of holy water, aimed to transform worshippers into heavenly citizens.

However, tensions with the Western Church grew. By 1054 CE, long-simmering disputes (over papal authority, the wording of the Nicene Creed, and other issues) culminated in the East–West Schism. Constantinople’s Patriarch and Rome’s Pope excommunicated each other, formalizing the split between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism. From then on, Byzantium headed the Orthodox world, drawing cultural lines between the Greek East and Latin West.

Missionaries carried Orthodox faith beyond Byzantine frontiers. Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century translated liturgy into Slavic languages. Soon Orthodox Christianity and Byzantine culture became foundational in Russia, Serbia, Bulgaria and other lands. Even today, Eastern Orthodox icons and liturgical traditions trace directly to this Byzantine heritage.

Decline and Fall

By the late 12th century, Byzantium was a rump state. The Fourth Crusade proved disastrous: instead of aiding Byzantium against Muslim foes, Crusaders in 1204 sacked Constantinople. They carved the empire into Latin states, Greek splinter kingdoms (Nicaea, Trebizond, Epirus), and Venetian possessions. It was not until 1261 that Michael VIII Palaiologos reunited the capital, but by then the state was a shadow of its glory.

In the 14th century the empire shrank further. Rapidly expanding Ottoman Turks encroached from Anatolia. A failed civil war, economic troubles, and repeated plagues weakened the state. Finally, after a 55-day siege in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II’s cannons blasted through Constantinople’s walls. On 29 May 1453 the city fell; the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, died in battle. Constantinople was renamed Istanbul and became the Ottoman capital, bringing an end to a thousand-year medieval empire.

The fall of Constantinople was a turning point in history. The Byzantine Empire’s disappearance shifted power to the Ottomans and, symbolically, marked the end of the ancient Roman legacy. Many Byzantines fled westward, carrying Greek manuscripts that would help ignite the Italian Renaissance. In the East, Orthodox Christians braced for centuries under Ottoman rule – yet Orthodox faith and Byzantine culture lived on in church traditions.

Enduring Legacy

Though politically gone, Byzantium’s legacy shaped the modern world. Its law proved especially long-lived: Western Europe’s rediscovery of Justinian’s Corpus Juris in the 11th–12th centuries sparked the revival of Roman law schools, influencing continental legal codes. In the Christian East, the Orthodox Church remained a bulwark of identity; its hierarchical and liturgical structures still mirror Byzantine patterns. Architecturally, the image of Hagia Sophia inspired Ottoman mosque design (and even later churches in Russia and Romania).

Culturally, Byzantine art endures in churches worldwide: the art of icon painting, gold mosaics and Orthodox hymnography all trace roots to Constantinople. Many Orthodox nations still celebrate saints and feasts from Byzantine calendars. Even political ideas, like the concept of a divinely-anointed Christian emperor, influenced medieval European thought (e.g. the idea of “symphony” of church and state). In sum, the Eastern Roman legacy lived on long after 1453 – in law, art, and faith spanning continents.

Conclusion

The Byzantine Empire stands as one of history’s most fascinating civilizations. Emerging from the shadow of Rome, Byzantium blended Roman governance, Greek culture and Christian faith into a unique society. It faced down armies from Persians to Slavs to Arabs, defended Europe from early Islamic conquests, and preserved classical knowledge through the Dark Ages. Its rulers like Justinian I dreamed of restoring Rome’s glory, and for a time they nearly succeeded. Byzantine emperors, saints, generals and artists left their mark in laws, churches and legends. Today, when one visits Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia, listens to Orthodox chants in Russia or reads a European law code, one is touching echoes of that Eastern Roman legacy.

Sources: Authoritative histories of Byzantium and others were consulted to ensure accuracy and depth. Each citation appears at the end of the relevant sentence.