Battle of Gettysburg (1863): Lee's Last Invasion

Explore the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863), a crucial turning point in the Civil War. Learn about Lee's invasion, Meade's defense, Pickett's Charge, and the Gettysburg Address.

4/20/2025

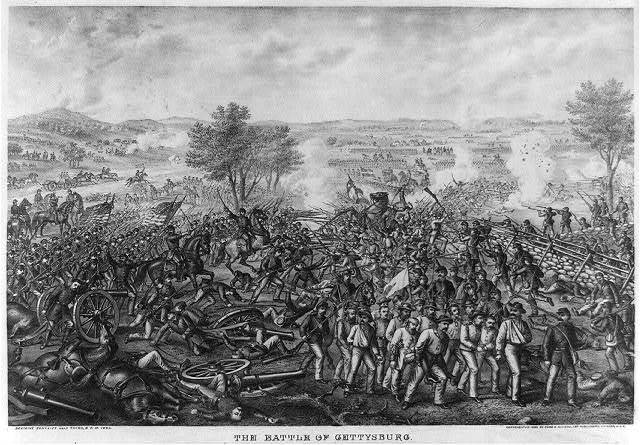

Gettysburg: The Epic Clash That Turned the Tide of the Civil War

The Battle of Gettysburg, fought across three pivotal days from July 1st to 3rd, 1863, in the rolling hills of Adams County, Pennsylvania, remains etched in the annals of American history as a watershed moment in the nation's most defining conflict. With an estimated toll exceeding 50,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing, this brutal and intense engagement stands as the bloodiest single battle of the entire Civil War. More than just a clash of arms, Gettysburg marked the decisive end to Confederate General Robert E. Lee's second ambitious attempt to invade the Northern states. This failure extinguished the Confederacy's aspirations of securing independence and significantly shifted the trajectory of the war. On one side stood the Union Army of the Potomac, led by the newly appointed General George G. Meade, tasked with defending the integrity of the nation. Opposing them was the formidable Army of Northern Virginia, under the command of the revered but ultimately thwarted General Robert E. Lee.

Seeds of Conflict: The American Civil War and the Gathering Storm

The American Civil War, which raged from 1861 to 1865, had its roots in fundamental and deeply entrenched disagreements that had been brewing for decades. At its core lay the contentious issue of slavery, intertwined with debates over states' rights and the very nature of the Union. By the mid-19th century, the question of whether slavery should be permitted to expand into the western territories had become the central point of contention, dividing the nation along ideological and economic lines. Northern states increasingly viewed slavery as a moral abomination, inconsistent with the ideals of liberty upon which the nation was founded. In contrast, Southern states fiercely defended the institution, arguing for its economic necessity and their right to self-determination.

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, a candidate whose platform opposed the expansion of slavery, served as the immediate trigger for the secession crisis. Fearing that their way of life was under threat, seven Southern states seceded from the Union even before Lincoln's inauguration in March 1861. By the time the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1861, four more states had joined the Confederacy, solidifying the division of the nation. After two grueling years of war, by the summer of 1863, a sense of war weariness had begun to permeate the North. Many in the Union were growing tired of the seemingly endless conflict and its mounting costs in lives and resources. Confederate General Robert E. Lee, keenly aware of this sentiment, believed that a significant portion of the Northern population, along with influential political figures, might be willing to concede defeat and seek a negotiated end to the war if the Confederacy could secure a major victory on Northern soil.

Lee's Gamble: The Confederate Invasion of the North

Following a stunning Confederate victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia in May 1863, General Robert E. Lee, emboldened by his army's success, decided to once again take the offensive and invade the North. This second invasion, the first having ended at Antietam the previous fall, was driven by a confluence of strategic, logistical, and political objectives.

One primary motivation was to relieve the pressure on the war-ravaged state of Virginia. By moving the conflict into Pennsylvania, Lee aimed to give Virginia's farmlands a much-needed respite from the devastation of war and allow his army to forage and acquire supplies from the richer Northern territories. Simultaneously, Lee hoped to draw Union forces away from the strategically vital Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi, which was under siege by Union General Ulysses S. Grant. A major victory on Northern soil could also potentially sway European powers, particularly Britain and France, to officially recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation. Furthermore, Lee aimed to bolster the cause of the Northern "Copperheads," a faction sympathetic to the South and advocating for peace, hoping to undermine support for President Lincoln's war efforts.

Strategically, Lee's campaign had ambitious objectives. He intended to shift the primary theater of the war away from Virginia and exert direct influence on Northern politicians, potentially compelling them to abandon their prosecution of the war. By threatening key Northern cities like Harrisburg, Pennsylvania's capital, or even Philadelphia, Lee hoped to inflict a significant blow to Northern morale and potentially force a negotiated settlement that would recognize Confederate independence. This invasion was a high-stakes gamble predicated on the belief that a decisive victory in the North could fundamentally alter the course of the war.

Collision Course: The Armies Converge at Gettysburg

In early June 1863, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commenced its northward movement from its positions around Fredericksburg, Virginia. By approximately June 15th, the vanguard of Lee's army had crossed the Potomac River, and by June 28th, they had reached the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, threatening the state capital of Harrisburg.

The Union Army of the Potomac, initially under the command of General Joseph Hooker, began to move in pursuit, striving to maintain a position between Lee's advancing forces and the vital Union capital of Washington D.C.. However, President Lincoln, dissatisfied with Hooker's cautious approach following the defeat at Chancellorsville, and amidst disagreements over the deployment of forces, relieved Hooker of command on June 28th. Major General George G. Meade was appointed as his successor just three days before the fateful encounter at Gettysburg.

The two great armies ultimately converged on the small crossroads town of Gettysburg almost by chance on the morning of July 1st. A Confederate division under Major General Henry Heth, part of Lieutenant General A.P. Hill's corps, was dispatched towards Gettysburg with the primary objective of acquiring much-needed supplies, particularly shoes, unaware of the significant presence of Union troops in the vicinity. This foraging expedition unexpectedly stumbled upon Brigadier General John Buford's Union cavalry, who had recognized the strategic importance of Gettysburg due to its convergence of numerous roads. This chance encounter ignited the first shots of what would become the most pivotal battle of the American Civil War.

Day One: July 1st, 1863 - The Opening Salvo

The first day of the Battle of Gettysburg commenced in the early morning hours of July 1st, around 5:30 AM, with initial skirmishes between Confederate and Union forces near Marsh Creek, to the northwest of Gettysburg. By 8:00 AM, General Heth's Confederate division was advancing on the town. They were met by the determined resistance of Brigadier General John Buford's Union cavalry, who skillfully utilized the terrain west of Gettysburg, particularly the ridges, to delay the Confederate advance and buy crucial time for Union infantry to arrive.

As the morning progressed, timely Union infantry reinforcements from the I and XI Corps began to arrive on the field, overseen by Major General John F. Reynolds, commanding the Left Wing of the Army of the Potomac. Tragically, shortly after his arrival and while directing his troops, General Reynolds was struck down and killed around 10:00 AM, a significant loss for the Union Army. General Abner Doubleday assumed command of the I Corps following Reynolds' death.

Throughout the day, Confederate forces continued to arrive, including reinforcements under Generals A.P. Hill and Richard Ewell. By late afternoon, the Confederate forces, significantly outnumbering the initial Union contingent with approximately 30,000 men against 20,000 Federals, launched a determined assault. The outnumbered Union troops fought fiercely but were eventually overwhelmed and forced to retreat through the town of Gettysburg. They regrouped and took up fortified positions on Cemetery Hill, located to the south of the town.

Later in the day, around 2:30 PM, General Lee arrived on the battlefield and recognized the strategic importance of Cemetery Hill. He provided General Ewell with the option to attack the Union forces on the hill if conditions were favorable for gaining and holding the position. However, Ewell chose not to pursue an immediate attack, a decision that has been debated by historians as a potentially missed opportunity for the Confederacy to press its advantage from the first day's fighting. By 4:00 PM, General Winfield S. Hancock arrived at Cemetery Hill, dispatched by General Meade to assess the situation and determine the best course of action.

Day Two: July 2nd, 1863 - The Struggle for High Ground

By the morning of July 2nd, the majority of both the Union and Confederate infantry forces had converged on the Gettysburg battlefield. The Union Army had established a strong defensive line south of Gettysburg, taking the shape of a fishhook. This line began on Culp's Hill, curved around Cemetery Hill, and extended south along Cemetery Ridge, anchoring at the base of Little Round Top.

General Lee's plan for the second day involved launching coordinated attacks on both ends of the Union line. The main thrust was directed at the Union left flank, with a heavy assault commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet's First Corps. Simultaneously, Confederate demonstrations against the Union right, near Culp's Hill and East Cemetery Hill, escalated into full-scale attacks later in the evening.

The second day witnessed some of the most intense and brutal fighting of the entire war, concentrated around key terrain features. Fierce engagements erupted at Devil's Den, a jumble of massive boulders; Little Round Top, a strategically vital hill at the southern end of the Union line; the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard, open areas that saw repeated assaults and counter-assaults; and along Cemetery Ridge, the backbone of the Union defense. The defense of Little Round Top, particularly the heroic stand of Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and the 20th Maine regiment, is a legendary tale of bravery and determination that is credited with saving the Union left flank.

Utilizing their advantageous interior lines, Union commanders like Major General Winfield S. Hancock were able to rapidly move reinforcements to critical points along the line, effectively blunting many of the Confederate advances. While the Confederates managed to gain ground in areas like Devil's Den and the Peach Orchard, they ultimately failed to dislodge the Union defenders from their crucial positions on Little Round Top and Cemetery Ridge as night fell. The Confederate assaults on Culp's Hill and East Cemetery Hill, though fierce, also did not succeed in breaking the Union's hold. The second day of battle resulted in extremely heavy losses for both armies, with casualties estimated at 9,000 or more on each side.

Day Three: July 3rd, 1863 - The Climactic Assault

The third day of the Battle of Gettysburg commenced with renewed fighting on Culp's Hill around 4:30 AM. Union artillery initiated a heavy bombardment aimed at retaking portions of the Confederate-held works on the lower slopes of the hill. The Confederates launched counterattacks, and fierce fighting continued for approximately seven hours, representing the longest sustained combat of the entire battle. However, the Union line held firm, preventing the Confederates from achieving their objectives on the Union right.

Having failed to dislodge the Union forces from either flank, General Lee made the fateful decision to attack the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Around 1:00 PM, a massive Confederate artillery barrage, involving an estimated 150 to 170 cannons, opened fire on the Union positions. This bombardment was likely the largest of the entire war. After approximately 15 minutes, about 80 Union cannons responded, engaging in a fierce counter-barrage. Despite the intensity, the Confederate artillery was critically low on ammunition, and the cannonade had little significant impact on the well-entrenched Union infantry.

At approximately 3:00 PM, following a lull in the artillery fire, around 10,500 to 12,500 Confederate soldiers emerged from the tree line on Seminary Ridge and began their advance across nearly three-quarters of a mile of open field towards the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. This ill-fated assault, famously known as Pickett's Charge, named after Major General George Pickett whose division formed a significant portion of the attacking force, was met with a devastating hail of Union rifle and artillery fire, including deadly canister shot at close range. Despite their bravery, only a small number of Confederates, primarily from Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead's brigade, managed to reach the crest of Cemetery Ridge, marking the "High Watermark of the Confederacy".

The assault proved to be a disastrous sacrifice for the Confederates, with casualties approaching 60 percent. The survivors were forced to retreat under the withering Union fire. When General Lee ordered Pickett to rally his division for a potential counterattack, Pickett's heartbroken reply was, "I have no division". The failure of Pickett's Charge effectively ended the Battle of Gettysburg, compelling Lee to begin preparations for a retreat back to Virginia.

After the Smoke Clears: Consequences and Casualties

The Battle of Gettysburg inflicted staggering losses on both the Union and Confederate armies. The Union Army sustained approximately 23,049 casualties, including 3,155 killed, 14,529 wounded, and 5,365 missing or captured. The Confederate Army's losses were even more severe, estimated at 28,063, comprising 3,903 killed, 18,735 wounded, and 5,425 missing or captured. The combined total of around 51,112 casualties made Gettysburg the bloodiest single battle of the American Civil War and in the history of warfare on the North American continent.

The small town of Gettysburg and its surrounding countryside bore the immediate and devastating impact of the battle. Homes and public buildings were transformed into makeshift hospitals, overflowing with wounded and dying soldiers from both sides. The once peaceful fields were littered with the bodies of men and horses, and the air was thick with the stench of death and decay. The civilian population, who had endured the terror of the battle, now faced the daunting task of caring for the wounded and burying the dead.

Following the repulse of Pickett's Charge, General Lee began to withdraw his battered army from Gettysburg on the evening of July 4th, embarking on a difficult retreat back towards Virginia. Union General Meade, despite securing a significant victory, chose not to aggressively pursue Lee's retreating forces. This decision proved controversial, drawing criticism from President Abraham Lincoln and others who believed it was a missed opportunity to potentially cripple Lee's army and perhaps even hasten the end of the war.

Army Strength Killed Wounded Missing/Captured Total Casualties Union 93,921 3,155 14,529 5,365 23,049 Confederate 71,699 3,903 18,735 5,425 28,063 Total 165,620 7,058 33,264 10,790 51,112

A Turning Point in History: The Significance of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg is widely regarded as the major turning point of the American Civil War. It marked the definitive end of General Lee's second and most ambitious attempt to invade the Northern states. The Union victory provided a much-needed and significant boost to Northern morale, ending a string of Confederate successes in the Eastern Theater and bolstering their confidence in ultimately winning the war. Conversely, the defeat at Gettysburg dealt a severe blow to the Confederacy, significantly diminishing their hopes for foreign recognition and severely weakening their military strength, particularly in terms of experienced leadership.

Later that year, in November 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered his now-iconic Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery. In his brief but profoundly moving speech, Lincoln eloquently redefined the purpose of the war, shifting the focus beyond simply preserving the Union to include the fight for human equality and "a new birth of freedom".

The Lay of the Land: Gettysburg's Geographical Importance

The town of Gettysburg's geographical location played a significant role in the unfolding of the battle. Situated at the intersection of numerous major roads, it served as a crucial hub in the regional transportation network. This convergence of roads, while not intentionally chosen by either army as a battleground, ultimately led to the unexpected meeting of the Union and Confederate forces.

Beyond its role as a transportation hub, the terrain surrounding Gettysburg profoundly influenced the course and outcome of the battle. The area's rolling terrain, punctuated by a series of north-south running ridges and several prominent rocky hills, provided natural defensive advantages. The Union Army, after being pushed back on the first day, established a strong defensive line along these elevated positions, including Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill, and the critical Little Round Top. These heights offered commanding views of the surrounding terrain and provided natural obstacles for attacking forces. Rocky outcroppings like Devil's Den further influenced the fighting, offering cover and strategic points for both sides. Interestingly, the thin soil on many of these hills made it difficult for Union soldiers to dig extensive entrenchments, forcing them to rely on existing stone walls and natural rock formations for cover.

The Union Army effectively leveraged the advantageous terrain, particularly the high ground, to establish a strong and resilient defensive line. Their fishhook-shaped formation along Cemetery Ridge and the surrounding hills allowed for better communication and the rapid transfer of troops to reinforce threatened areas, ultimately playing a crucial role in repelling the repeated Confederate assaults.

Echoes of the Past: Historical Interpretations and Debates

The Battle of Gettysburg is almost universally recognized as a pivotal turning point in the American Civil War. However, some historians offer alternative perspectives, suggesting that while Gettysburg was undoubtedly significant, other events, such as the Union's capture of Vicksburg on the very next day, were equally or perhaps even more crucial in determining the war's outcome. The fall of Vicksburg gave the Union control of the entire Mississippi River, effectively splitting the Confederacy in two, a strategic blow of immense magnitude.

The Battle of Gettysburg has also been the subject of intense scrutiny regarding the strategic and tactical decisions made by the commanders of both armies. Confederate General Robert E. Lee's decision to invade Pennsylvania in the first place has been questioned by some historians, who argue that resources might have been better allocated to the Western Theater. The performance of Lieutenant General James Longstreet, particularly his perceived slowness in executing Lee's orders on the second day, has also been a source of debate. Additionally, the absence of General J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry for a significant period leading up to and during the early stages of the battle deprived Lee of vital intelligence about Union troop movements, a crucial factor that may have contributed to the Confederate defeat. Lee himself acknowledged his responsibility for the outcome of the battle. On the Union side, General Meade's decision not to launch a vigorous pursuit of Lee's retreating army has been a subject of historical discussion, with some arguing that it was a missed opportunity to inflict a decisive blow on the Confederacy.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

The Battle of Gettysburg stands as a landmark event in American history, a brutal and decisive clash that significantly altered the course of the Civil War. The Union victory marked the end of Confederate ambitions to invade the North and dealt a crippling blow to their hopes for independence. Coupled with the Union's triumph at Vicksburg, it irrevocably shifted the momentum of the war in favor of the North. The Gettysburg battlefield stands today as a solemn reminder of the immense sacrifices made by soldiers on both sides, and President Lincoln's Gettysburg Address continues to inspire with its powerful message of unity, equality, and the enduring principles upon which the United States was founded.